A Conversation with Three Roswell Artists

By Willy Carleton

Justin Richel, Endless Column (Toast), 2017–18, urethane plastic, acrylic, 36 x 4 x 4 inches. Photo courtesy of Justin Richel.

With my stomach rumbling and an $120,000-duct-taped banana suspended on the canvas of global headlines, I head to the Roswell Artist in Residency (RAiR) campus to share a meal with several artists, visit their studios, and learn how food shapes their work. Founded in 1967 by Roswell businessman and artist Don Anderson, today RAiR houses six full-time artists from around the world on its fifty-acre campus and has helped put the small town in New Mexico’s high plains on the fine art map. RAiR director Larry Bob Phillips greets me at the residency campus and welcomes me into the house where he lives with his wife and fellow artist, Tamara Zibners, and their one-year-old son. Artists Micheal Waugh, Justin Richel, and Jeremy Howe, each of whom approaches food from a different angle in their work, soon join us, and we sit down to a salad and steaming red chile enchiladas.

“Why food?” I ask in reference to their artwork as we dig into the meal. The chilly purple twilight transforms into a frigid and star-filled December night as this simple query leads to a long conversation yielding more complex and nuanced questions about how we think about consumption, preservation, and the synthetic chemicals ubiquitous in all stages of industrial food systems.

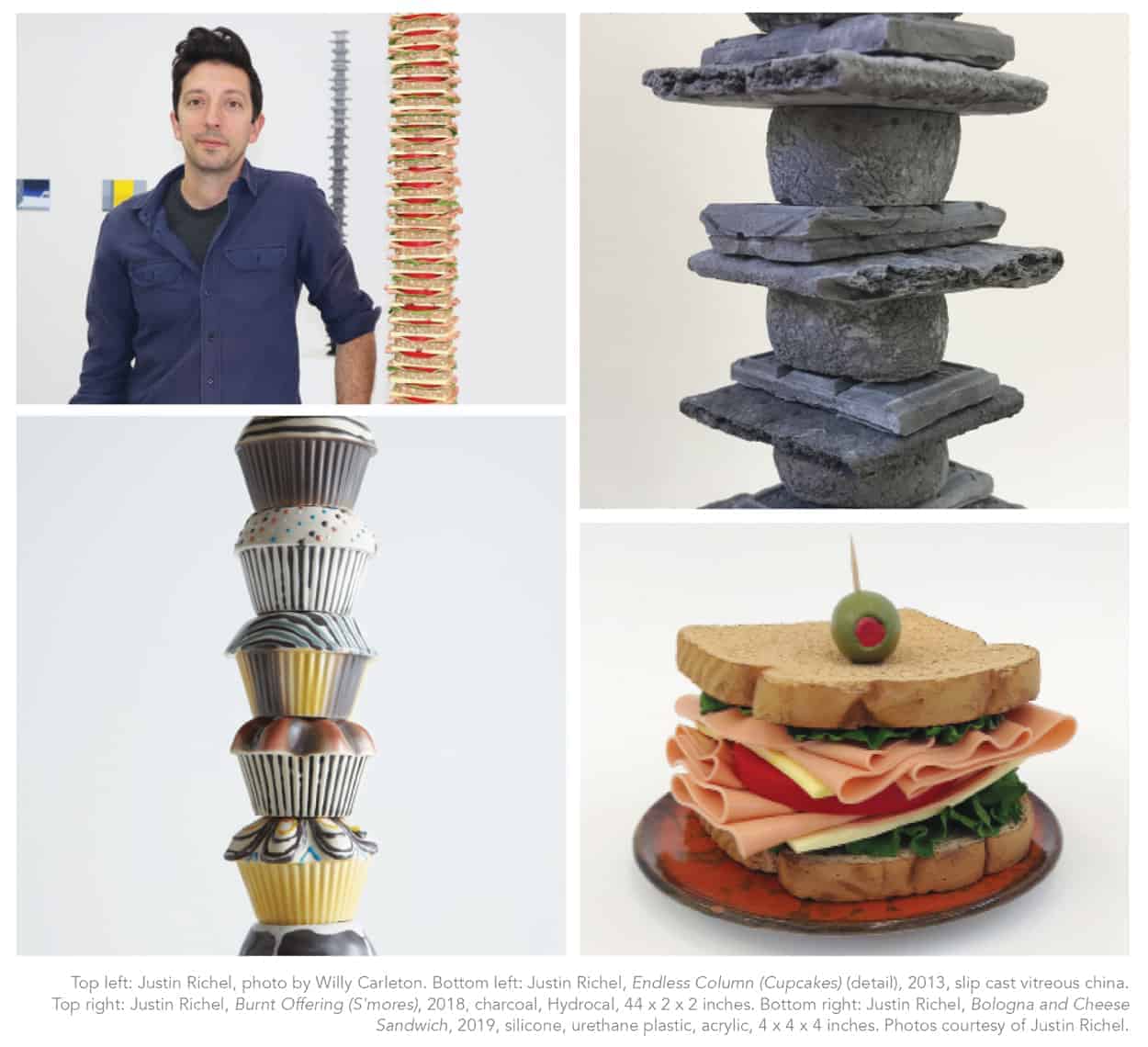

“We’ve gotten really far away from what food is,” explains RAiR resident Justin Richel, running his fingers across the stubble on his chin. Richel, who raised food for himself for over a decade in rural Maine, laments the loss of connection to food he sees in today’s grocery stores. He views industrial food as an expedient convenience that we have, as a society, bought into and trusted in despite costs to human and environmental health that we are only beginning to understand. Through his work, he has tried to reflect this loss of connection and misplaced trust in industrial food through columns of meticulously painted plastic forms, such as his 2016–17 Tall Order (Bologna and Cheese), a sculpture of a ten-foot tall, 1:1 scale bologna sandwich.

Impossible to ingest in both its material (silicone, urethane plastic, acrylic) and size, Tall Order comically jabs at the near inedibility of industrial food, its unnatural preservability, and the overconsumption it both caters to and drives. Yet behind its irreverent and absurd parody, the plastic sandwich tower represents an earnest lament for the loss of a relationship to the foods that can truly sustain us and, with that, the loss of a sense of sacredness in our daily meals.

Justin Richel, Tall Order (Bologna and Cheese), 2016–17, silicone, acrylic, urethane plastic, 108 x 4 x 4 inches. Photo courtesy of Justin Richel.

“I think of [Tall Order] as a failed monument,” Richel explains. “It’s heavily preserved garbage in this repeating form. It’s an obelisk to something, it’s phallic in nature, so you know it’s that patriarchal viewpoint.

. . . But it’s a failed monument to a failed society of wrong turns.”

“God, that’s wonderful and totally depressing,” responds Roswell Museum and Art Center planetarium director Jeremy Howe, smiling as he looks up from his plate of enchiladas.

“Yeah, I know, it’s depressing as shit, but, yeah, it makes me laugh,” Richel continues, his expression part wry smile and part prolonged sigh. “That’s the thing. I see a lot of humor in it too. I also see a return to better ways in it, too, for anyone who’s really conscious.” Then Richel’s eyes grow a shade more serious. “I’m trying to wake people up through the ridiculousness of a ten-foot-tall sandwich, but some people tell me they get hungry when they see it. I go, ‘That’s messed up. I want to throw up when I see it, but okay. I’m trying to wake you up the best I know how without hitting you over the head with it too. I don’t want to preach to you . . . but a ten-foot-tall sandwich should get you thinking.’”

We chuckle, but a contemplative silence descends on the table as we return to our plates, digesting Richel’s suggestion that perhaps the larger tragedy of the sculpture is not the message it carries but the ways that message has been lost on many who view it.

The conversation shifts to Howe’s work, which, unlike Richel’s use of nonfood to depict food, uses food products to depict more abstract designs. Using a range of materials, from condensed milk and seaweed and chile powder to cream cheese filling and Pepto-Bismol and Vegamite, Howe repurposes preservative-laden industrial foods as art materials. He has produced more than fifty canvases of richly colored and textured designs, transforming the ubiquitous and unhealthy into unique, abstract, and aesthetically pleasing designs. He works with the preservatives and the chemical properties to create new forms, new designs, and new meanings. “They are all dynamic and in various processes of chemical reaction, and you have to just embrace that.” For Howe, embracing these materials was driven by a sense of novelty and experiment, but implicit to the designs is the notion that such materials—the main or only form of sustenance that many Americans have access to—might function better as art than food in a more equitable world.

“It was just pure art material,” Howe explains of the first time he considered using food ingredients in his work, fifteen years ago. “It was really nice as an art material to start with, then I was aware of all the horrible preservatives, and then I thought, well, great, this is fantastic. . . . We call it food but it’s really a better material to put on a canvas. It just lasts because the ants won’t even get it and the rats won’t even get it.”

“It’s poison!” he recalls realizing when he noticed that not even the rats were touching a recent exhibit in which he covered a large square space on the floor entirely with artificial cheese powder. “Then, that led to a whole different thought,” he adds, “which is that we’re eating poison all the time.”

Unlike the food-centered works of Richel and Howe, food is only implied, not used or represented, in the recent work of Michael Waugh. Waugh, who descends from a long line of farmers in New England, is currently a RAiR resident working on a series of drawings depicting a man, a dog, and birds in a bucolic riverside scene, with the drawn lines of the images entirely formed from the words of Rachel Carson’s 1962 Silent Spring. For Waugh, this ancient artistic form, known as micrography, creates a conceptual relationship between the text and the image that can give greater meaning to both. By using Silent Spring, a landmark book that awakened the world to the ecological harm of chemicals such as DDT and helped spur the pushback against chemical pesticides and herbicides that led to the emergence of the modern organic farming movement, Waugh hopes to engage his audience with the long-standing conversation on the costs of synthetic chemicals in our food system. “As much as I want people to read Silent Spring,” he explains, “I want this to be a conversation starter wherever it goes. . . . Just getting people talking in an expansive way is important.”

The following day, the conversation continues as I tour each artist’s studio. I notice notes of redemption—subtle, hard-fought, and qualified—running through each artist’s work, notes that had not been prominent in the conversation the night before. I am particularly struck by one of Richel’s more recent works, Burnt Offering (2018), which is a plaster- and charcoal-dusted tower of blackened s’mores. Four feet tall and vaguely resembling an altar, the sculpture reflects a collective attempt at forgiveness, Richel explains, albeit a childishly clumsy and misguided one, for the type of grotesqueness and unabashed self-aggrandizement depicted in Tall Order. “You are not forgiven,” Richel laughed, as he imagined it as an offering to a deity, and then asked, “What god would want this?” And yet, behind this dry joke, the self-effacing sculpture suggests a drive for humility and a search for atonement by and for the “society of wrong turns.”

If there is a common thread among these three artists’ approaches to food and art, it might be their concern for the rise in a reliance on synthetic chemicals—from pesticides to artificial preservatives—in our industrial food system. More broadly, there is a hope inherent to each artist’s work that the power of art—whether through Howe’s playful, mesmerizing, and abstract work, Richel’s comedic and grotesque “monuments to garbage,” or Waugh’s intricate and novelistic landscapes—can inspire new ways to look at what has been long in plain sight. From an environmental text first published fifty-eight years ago to a packet of cream cheese or a bologna sandwich, these artists add urgency and new meaning to what has become familiar. Taken together, the chemistry of our current foodscape can be rearranged or reexamined to provide new vantages, at times light-hearted and at times somber, into the immense beauty of the natural world and our tragedy-prone relationship to it.

Edible celebrates New Mexico's food culture, season by season. We believe that knowing where our food comes from is a powerful thing. With our high-quality, aesthetically pleasing and informative publication, we inspire readers to support and celebrate the growers, producers, chefs, beverage and food artisans, and other food professionals in our community.