A Story of Blue Corn and Place

By Cassidy A. Tawse-Garcia

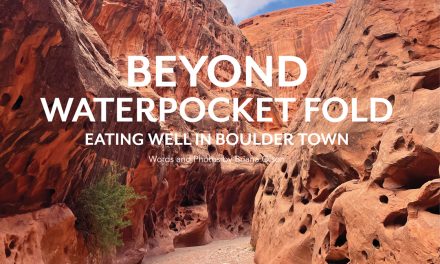

Blue corn harvest at Lorenzo Candelaria’s farm. Photo by Stephanie Cameron.

My father dropped me off at her house each morning cocooned in a white bedspread with pink flowers she bought for me. Nana could still carry me then. I was small, and she was healthy. As her goddaughter, she claimed me as what she always wanted but never had: a girl. Most mornings, I uncurled my limbs, wiped the sleep from my eyes, and wandered through the small house toward her smells. Cinnamon pinched in coffee, tomatoes stewing in rice, and holy water. Most often I would find her standing at the stove, presiding over her kingdom—frijol her court, Jesus her advisor. After a kiss and the Lord’s Prayer, she would serve me a floral china mug filled with milky-warm atole—the blue corn porridge of her homeland.

The author and her nana, Henrietta Cochon Martinez,

enjoying their backyard in SE Denver, circa 1993.

In a 1987 travel article from the New York Times, Susan Benner wrote of blue corn, “The colors and textures seemed as Southwestern as adobe. . . . That night I felt as if I were eating earth—not dirt, but food that was somehow connected to the richness of earth.” While much has changed in land and agriculture since the year that article was published, Benner’s testament of blue corn’s relation with place remains true today.

Maize (Zea mays) can be grouped into two broad categories: that harvested young (usually sweet corn) and eaten fresh, and that harvested mature (including field corn, flint corn, and flour corn) and eaten dry. Flour and flint varieties of corn, such as blue corn, are dried, roasted, often nixtamalized (treated with an alkali), and prepared in various forms of flours, meals, posole (hominy), and chicos. They’re used to make foods such as Hopi piki bread (a thin-layered oven bread), tortillas, pancakes, and porridge. This porridge is what the Hopi call wataca, the Diné (Navajo) call mush, Puebloan people call chaquehue, and what I learned from my godmother as atole, a word that comes from Nahuatl. The blue corn kernels are roasted prior to milling, giving the hot cereal a nutty, earthy flavor. In its simplest form, atole is a porridge of toasted ground cornmeal, water, and sometimes salt or sweetener, often thin enough to drink, but other times thick like polenta.

To understand the cultural place blue corn mush holds in the American Southwest is to understand the movement of peoples and seeds across space and time. The domestication of maize began nine or ten thousand years ago in what is now southern Mexico and Guatemala. Over time, corn spread across the Americas with the movement of Indigenous peoples. Ancestral Puebloans began to establish semipermanent settlements where they could cultivate corn as early as 2000 BCE. The need for corn to be cultivated in rows led to advances in irrigation techniques, like ditches for rainwater runoff, starting around 250 CE.

When the first Spanish colonizers came into contact with Puebloan and Hopi peoples around 1540 CE, they had been cultivating and tending to corn—including blue corn—beans, and squash in a symbiotic relationship with the lands, each other, and nonhuman relations for hundreds of generations. These first Spanish colonizers reported seeing Native people spreading cornmeal around their doorways to ward off the conquistadores. The Spanish most likely also witnessed Hopi peoples harvesting, drying, storing, decobbing, roasting, and grinding their corn into wataca, in a fashion similar to what they do today.

Hispano settlers claimed land along the Rio Grande and its tributaries. They adopted Native farming and irrigation practices while integrating methods for arid agriculture learned from the Moors, who brought acequia systems to the Sierra Nevada of southern Spain from North Africa in the eighth century. Thus, atole is an adaptation of Indigenous foodways and ways of knowing that includes the cultural building of acequia communities we see today.

From top left, clockwise: Blue corn bin; Michael Kotutwa Johnson in field; an ear of blue corn; stone wind protectors for bean, squash, and melon seedlings; corn grinders.

Michael Kotutwa Johnson, with a strong handshake and warm smile, introduces himself as a 250th-generation farmer. I think I hear him wrong . . . 250 generations? “To be Hopi is to be a farmer, and to be a farmer is to be Hopi,” Johnson explains. He holds a PhD in natural resource management, a master’s degree in public policy, and a bachelor’s degree in agricultural science. As an assistant specialist for the Indigenous Resilience Center at the University of Arizona in Tucson, he is currently bringing Indigenous practices of dryland agriculture into the fold of USDA climate-smart techniques for farming in arid landscapes. On Johnson’s family farm, located on the Hopi reservation in northeastern Arizona, he cultivates corn of many varieties from seeds his mother and sisters keep. The Hopi are a matrilineal society, where the women are seed breeders, dictating harvests by the seeds they choose to keep and cultivate from season to season.

Johnson tells me that Hopi farmers plant corn seeds together in companion bundles—a dozen seeds to one hole, spaced six to eight feet apart. One of the Hopi people’s cultural and spiritual teachings is that seeds should not be lonely when they are sprouting. Where modern corn planting would dictate seeds be planted only inches under the earth, Johnson sometimes plants seeds fourteen inches deep. This is so the seeds can reach the water table—essential to dryland farming, a practice where crops are watered through natural rainfall as opposed to irrigation. “With the recent drought, these practices have become harder,” Johnson tells me. “But two good rains, and the corn will grow tall.”

For Hopi people, corn is not just corn. Corn is part of who they are. Different varieties and colors accompany different cultural and religious ceremonies; corn is present at every birth, death, and wedding. These practices stem from the Hopi origin story: Johnson explains to me that the Guardian Spirit of his people, Màasaw, led them north to where they call home today. The spirit offered gifts to the different clans: wood that became the Hopi planting stick, a dried gourd of water, and a small ear of blue corn. These gifts form the basis of Hopi spirituality, and connection to place.

Johnson is ultimately concerned with the “revitalization of the American Indian food system.” For him, this is the process of elevating Indigenous ways of knowing as a “value system and culture that allows us to bounce back.” That is to say, for Johnson, corn, especially blue corn, is not merely a food; it represents “humility, patience, and endurance” in the face of cultural and climate threats.

Domesticated corn is the daughter of teocintle, also called teosinte, a wild, flowering perennial whose “cobs” fit in the palm of one’s hand. I know this because on a very rainy day this past October, farmer and seed keeper Ron Boyd removed a small jar from his corn altar—a mixture of iconography, art, and seeds honoring and made of maize—and emptied its contents into my hand. The teocintle that I held was cultivated on Boyd’s land, one hundred acres along the Rio Grande in La Villita. What is now a fifteen-minute drive north from Española was at one time a distinct, thriving farm community, with the largest acequia madre in the state.

Ron Boyd and eight-row Delaware Flint. Photos by Sylvia Tawse.

“I do not grow Hopi corn,” Boyd explains to my mom and me as we stand, soggy with rare fall rain, in one of his cornfields. “Hopi corn can only be from Hopi, by Hopi. I grow blue corn.” Boyd was given his first blue corn seed thirty-seven years ago. (It is a cultural practice of the Hopi to share corn seeds for keeping and planting, but never to sell them.) Today, he grows two varieties of corn for a seed company, Baker Creek Heirloom Seeds, including the midnight-blue eight-row Delaware Flint, referring to the eight rows of kernels around the circumference of the cob. Ancestors of this variety began to travel with Indigenous traders from the Rio Grande Valley up the Mississippi River by 1000 CE, and were eventually cultivated by the Delaware, or Lenape, people of the northeastern woodlands.

Boyd harvests his corn with a Chinese corn picker, adapted to collect cobs mere inches from the ground, as the Delaware Flint has a short stalk. But he still holds an annual harvest party, where the community is invited out to share in the harvest. “There is a whole lot of interest in ‘I want to do it with ya,’” he muses. So while this farmer does sell corn seed, the maize he holds most special is the blue corn that he and his wife toast and grind in their home kitchen to make atole.

Back in his kitchen, examining the teocintle, Boyd says, “The magic that started with this, and developed into corn as we know it, and the multitude of colors and varieties it came to be; it’s just unknowable.” And perhaps that is it. Like the corn dances of the Pueblo peoples along the Rio Grande or the Hopi origin story, blue corn is a weaving of culture, spirit, and practice, a process that cannot be fully understood on a timetable. For those who cultivate it, who know it intimately, the spirit of blue corn’s connection to place may be enough.

Blue corn mush brings to mind family and connection for dietician Denee Bex. “We always had it at my grandmother’s on the weekends, for the Super Bowl, or graduation,” she tells me over the phone from her home on the Navajo Nation. Through her personal business, Tumbleweed Nutrition, Bex educates people on the benefits of Indigenous foodways. “It’s important for Indigenous people to see folks like them giving health advice,” she adds. Bex tells me she is one of only about three hundred Indigenous registered dieticians in the United States, and the only Navajo dietician (that she knows of) to own a consulting business. Delivering culturally relevant nutrition education to tribal organizations is the basis of Bex’s consulting. And singing the praises of blue corn mush is part of that ethic.

“Traditional foods signify the connection we have,” Bex explains. “For Navajo, this is our idea of taking just enough from the land, for what you need to be healthy.” On the day we speak, Bex is working on scaling up a blue corn mush recipe to three thousand servings, for the Navajo nation’s public schools. Part of her work is to battle the rhetoric of what it means to be healthy and Native. “When we make blue corn mush, we make it in large quantities to serve family and friends . . . [for us,] blue corn is doing something together.”

Lorenzo Candelaria and his blue corn. Photos by Stephanie Cameron.

The addition of juniper ash sets Navajo blue corn mush apart from atole. Considered a healing plant to the Diné, juniper is used in ceremonial practices for cleansing. While Bex cannot be sure how and when people started adding juniper ash to blue corn porridge, she postulates that it relates to this spiritual connection. As a dietician, she knows that juniper ash, an alkaline substance, adds nutrition to this simple food. Nixtamalization, the process of adding alkalinity to corn while cooking, raises the pH of the water, opening up the cell walls of the corn to release more nutrients like B vitamins, proteins, and amino acids. Blue corn is said to have up to 20 percent more protein than white or yellow corn and is high in antioxidants due to the flavonoid anthocyanin, which gives the plant its purple-blue hue.

When I drank atole as a child, it was most often a compromise. Each day I spent with my great-aunt and godmother Henrietta “Nana” Cachon-Martinez meant a day we went to church. “Our bodies were meant to be pure for Christ,” Nana would explain. But my five-year-old belly did not understand why Christ needed me to go without breakfast. Our deal became a cup of atole, liquid enough to drink, and I would attempt to sit still through mass.

Today when I make atole, it is a ritual of the changing season, a practice that starts at the first turn of the cottonwoods and continues through the frozen mornings of winter into the thaw of spring. Making atole often happens in the dark of early morning, by myself, before any words have been spoken to the day. It instills a deep vein of remembering for when Nana was alive.

Since making New Mexico my home three years ago, the concept of querencia has often been on my mind. I think of this word, which does not have a direct translation to English, as meaning “being so tied to a place that the place becomes inseparable from you.” Even when you leave that place, it continues to exist inside you, permeating the way you conceive of and engage with the world.

Each time I go to Taos, I make the pilgrimage to Arroyo Hondo to see the house where Nana grew up. It is located across the highway from the only businesses in town—a gas station and a liquor store. Her mother bought the house from a Sears, Roebuck catalog in the 1940s with money from the state, paid in exchange for the family allowing their adobe to be torn down to make way for the new two-lane highway. From the house, I travel down a dusty road through the deep gash in the Taos plateau known as the Gorge to visit the Rio Grande.

I walk along the banks, taking in the trickling of Vasquez Creek merging into the Rio Grande, and think of Nana and her querencia. How she carried it with her all the way to Denver and shared its stories and tastes with me through my childhood. I think of my own querencia, and how it feels liminal to come “home” to a place where I never lived before. But by being here, I feel closer than ever to the life lessons Nana imparted to me.

Lorenzo Candelaria making atole, photo by Cassidy A. Tawse-Garcia.

On a sunny late fall morning, with coffee and supplies in hand, I head to Lorenzo Candelaria’s farm, situated along the Rio Grande and Atrisco Ditch in the South Valley of Albuquerque. On a camp stove, the petite man, whom I have only ever known to wear overalls, a flannel shirt, and a pañuelo, sets to work making me breakfast.

“We are the earth, and the earth is us,” Candelaria has told me more than once. This seventh-generation farmer cultivates food on the remains of the land grant his family settled 350 years ago. It is now enmeshed in a rapidly modernizing neighborhood and world. The time he gives to the cultivation of plants and friendships alike is humbling. Nothing about Candelaria’s life choices is fast. He is fond of telling a story of how he was born prematurely on his grandmother’s ranch in the Magdalena Mountains, and in order to keep him alive, his grandmother incubated him in her earthen clay horno. “I am a child of my mother, and madre tierra,” he tells me.

Candelaria has instructed me on the exact ingredients to bring for his everyday breakfast, atole made with night-blue corn grown in the fields next to where we now stand. These components—salt, cinnamon, milk, and honey—are now laid out next to him and the stove. He has brought to the operation his toasted blue cornmeal, from corn roasted in his home oven, cookie sheet by cookie sheet laden with kernels, during the previous winter. Once the water comes to a boil, he moves with intention. We have premixed half a cup of toasted cornmeal with water to make a paste, and when I hand him the slurry, he dumps it into the boiling water, made into a funnel by the spinning of his spoon. We add a stick of canela and a pinch of salt. “You don’t want to stop stirring,” he instructs. The water absorbs the blue corn mixture in a gray cloud, thick with grain. After about a minute, white bubbles begin to appear on the surface. “That’s the starch,” Candelaria informs me. “When the bubbles are gone, we know it has cooked enough.”

A minute or two later, the white foam subsides and Candelaria ceases his circular motion. He covers the saucepot while we sit on worn lawn furniture and take in the cool sunshine of this slow Wednesday. After the requisite pause, and a soulful conversation—because that is the only kind Candelaria has—we duck back into the makeshift kitchen. He pours the mixture into a bowl and invites me to top it with a splash of cream and honey. The cream slops atop the porridge and reveals itself in a white, curved line reminiscent of a heart.

Blue corn mush, unadorned beyond salt, canela, and just a little something sweet, tastes of the land from which it came, the rain that nourished it, the hands that planted it, the dry earth who supported its stalks, the hard freeze that signaled its time for harvest, the cob that acted as home for its drying kernels, and above all, the nutty aroma of toasted kernels. This journey from seed to meal is where the labor takes place. So that, in the home, blue corn is free to simply tell its story of family and land and place, of gratitude and knowing. It is a story written in home kitchens, across tables, on cold winter mornings, in small fields with and without water, across the Southwest. The blue/gray/purple porridge is nourishment that is also knowledge-making. In its simplest form, atole is a child finding comfort in the liminal space of love presented in food.

Love in a cup, photo by Cassidy A. Tawse-Garcia.

Lorenzo’s Atole

Instructions

- *In general, use a 4:1 ratio (liquid to cornmeal)

- Bring 1 cup water to a boil in a small saucepan.

- Separately, add 1/4 cup cornmeal to 1/2 cup cold water, creating a slurry. Set aside.

- When water comes to a boil, stir in cornmeal.

- Continue stirring constantly for 1–2 minutes. (Smell it! The toasted flavor will come through.)

- When a white foam appears on the top, continue stirring for another 1–2 minutes, until the foam dissipates. (This is the starch being converted into sugars).

- Add a pinch of salt and either 1/2 stick or 1/2 teaspoon of cinnamon, and continue stirring for about a minute more, until the liquid starts to thicken.

- Turn off the heat; cover saucepan with lid. Let sit for 5 minutes.

- Season, to taste, with milk, butter, more cinnamon, and the sweetener of your choice (Lorenzo recommends honey). Enjoy.

Notes

Edible celebrates New Mexico's food culture, season by season. We believe that knowing where our food comes from is a powerful thing. With our high-quality, aesthetically pleasing and informative publication, we inspire readers to support and celebrate the growers, producers, chefs, beverage and food artisans, and other food professionals in our community.