Cultivating Cannabis in the Land of Enchantment

By Briana Olson

Photo by Stephanie Cameron.

“What can’t hemp do?” my partner asked when I texted him someone’s claim that, because hemp is referenced in the Bible, some users of hemp products find it a “truly spiritual experience.” I laughed, but I had to think for a minute. Hemp can be used to make textiles and rope. It can be used to produce building materials, animal bedding, paper, and fuel. It can be used in the fabrication of bioplastics. It’s said to sequester more carbon than other crops, and has been used in phytoremediation, perhaps most famously in Chernobyl. Its seeds can be eaten or pressed into oil. And its various chemical constituents—most notably, at least for now, cannabidiol (CBD)—can be extracted and used in a myriad of topical and edible products that users believe to have a dizzying array of beneficial effects.

“It can’t kill people,” I finally replied, with relative certainty.

If I were speaking of almost any other crop, this would be an insignificant statement. But hemp has been conflated with marijuana since the passage of the Marijuana Tax Stamp Act of 1937, and marijuana, since 1970, has been listed as a Schedule 1 drug in the Controlled Substances Act, meaning that in addition to being characterized as having a high potential for abuse and no known medical value, it is characterized as unsafe to use even under medical supervision. Theories abound as to the motivations behind both pieces of legislation, but there is no dispute about the outcome: virtually no hemp was produced in the United States from the end of World War II to 2014.

First, The Word

To enable the cultivation of hemp, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) first had to define it.

“I was ready to retire,” says Kathi Caldwell, well-known among Albuquerque farmers for her years running Rio Valley Greenhouses, where she started thousands of the vegetables that made their way into the local produce circuit. “I used to tell my husband I was going to grow hemp; he’d say that’s never gonna happen in our lifetimes.” But then it did.

The 2014 Farm Bill opened the door by allowing licensed growers to research hemp. Four years later, the next farm bill legalized commercial production. According to the 2018 Farm Bill, hemp is “the plant Cannabis sativa L. and any part of that plant, including the seeds thereof and all derivatives, extracts, cannabinoids, isomers, acids, salts, and salts of isomers, whether growing or not, with a delta-9 tetrahydrocannabinol concentration of not more than 0.3 percent on a dry weight basis.” Translation: hemp is cannabis with less than 0.3 percent of the psychoactive compound tetrahydrocannabinol, more commonly known as THC.

The New Mexico Department of Agriculture issued the first license to grow hemp in December 2018. As of October 2019, when I speak with Brad Lewis, administrator of the hemp program for the NMDA, four hundred licenses have been issued, approving 7,500 acres of outdoor and one hundred acres of indoor growing.

“It’s kind of a bucket list thing for me,” says Caldwell. So, instead of retiring, she secured two of those licenses, teamed up with experienced growers, and transitioned her greenhouse space to hemp.

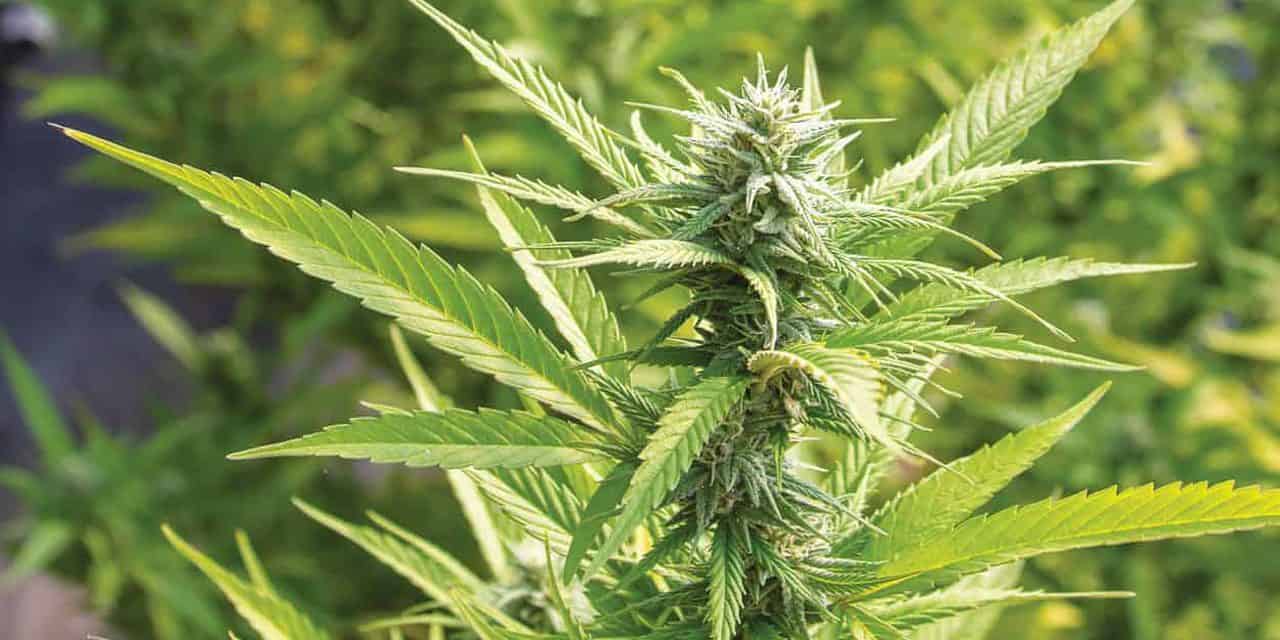

A one-night freeze is forecast the afternoon I visit Caldwell at Atrisco Valley Farm, and a few workers are busy harvesting the last of the tomatoes and peppers from the raised beds out front. I peek into a greenhouse and see a small forest of what look like mature, robust marijuana plants—mothers, I’ll learn, from which hundreds of clones have been cut for sale. Inside the house, young people stand trimming flowers (the plump, hairy buds produced by female cannabis plants). In the next room, dozens of fuzzy green flower-laden stalks hang upside down, drying. The intensely pungent, skunky odor of hemp—identical in profile to marijuana—permeates the house.

It should not be surprising that plants of the same species would be very, very similar. Yet there has been so much effort to distinguish between marijuana and hemp that I had come to perceive them as fundamentally different. So it comes as something of a shock to realize that the naked eye (and nose) can’t tell them apart.

“The FDA’s definition is not botanical,” confirms Dr. Rich Richins of Rio Grande Analytics, one of two in-state facilities approved by the NMDA to test the THC content of hemp and hemp products. “It’s the same plant.”

That doesn’t mean Richins doesn’t take the testing process seriously. Nor does it mean the plant should be feared. What it does mean is that if you want to grow ten acres of hemp, you might want to hire security. (It turns out that former governor Susana Martinez’s concern about hemp being confused for marijuana wasn’t entirely off the mark— but it’s thieves, not law enforcement, who are having trouble telling the crops apart. In October, a man with a truckload of stolen hemp, which he’d mistaken for marijuana, was arrested in Chaves County.)

Hemp grown and delivered by McClain Greenhouses/Fresh Grown Systems. Photo by Manuel Ordaz, owner/operator, Fresh Grown Systems.

The Search for Seed

For decades, cannabis advocates have lamented the dearth of research that resulted from the criminalization of both marijuana and hemp. For armchair philosophers (and even for legislators), the lack of hard data means debates over cannabis have often devolved into defenders proclaiming cannabis a panacea (Cannabis cures Alzheimer’s! Cancer! Intellectual atrophy!) and opponents clutching at dubious correlations between THC and insanity. For farmers raising hemp for the first time, the long prohibition translates into a more hands-on problem: seed stock.

To acquire seed in 2014, when the first research permits were issued, Colorado farmer and architect Arnie Valdez had to order from a co-op in France. Valdez, who’s working on a permaculture design at Rezolana Farms, views hemp as “kind of a miracle crop,” not because of its chemical properties, but because of its versatility and heartiness. On top of frustrating negotiations with the DEA, Valdez says, the seed imported from France was protected, so it had to be repurchased every year. In 2016, he bought from a local Colorado grower, and since then has been using a local mix.

Thanks largely to Susana Martinez, New Mexico ran no pilot programs on hemp between 2014 and 2018, so there was no local New Mexico seed.

“Most crops, like corn,” says Stephen Sisneros of New Mexico Hemp, “go through several hundred generations before becoming a stable commercial crop.” With hemp, farmers are dealing with firstand second-generation phenotypes. The genetics are unstable, and the plants are often unpredictable. Sisneros, who works with Caldwell at Atrisco Valley Farm, bought seed through Colorado-based Salida Hemp. There are seven expressions of the phenotype, he says—red stalks, green stalks, bushy plants, tall plants—but “so far, none of them have gone hot.”

“Hot” is the industry term for cannabis plants whose THC content exceeds 0.3 percent. Until marijuana is legalized in New Mexico, having a crop “go hot” is the worst-case scenario for a hemp farmer; the entire crop must be destroyed, so it’s equivalent to (and possibly more expensive than) total crop failure.

No one I’ve spoken to had to destroy crops, and Richins says he’d estimate a ninety-five percent pass rate on tests run by Rio Grande Analytics, but everyone seems to have heard stories of a farmer who’s lost ten acres or ninety acres or even four hundred acres due to the crop “going hot.” Environmental factors matter—heat and water stress can raise the level of THC—but it starts with the seed.

“Seed is the biggest cost,” says Manny Ordaz of Fresh Grown Systems. Ordaz, who raised cannabis in Colorado before returning to New Mexico to grow hemp, paid a dollar a seed to Oregon growers who also gave him pointers on the crop. In 2019, he sold “developed root systems,” some seedlings and some clones, to multi-generation farmers who raised about two hundred acres around the state. This winter, instead of taking a seasonal break, he’s running a seed project, raising three thousand plants to strengthen his genetics.

“You’re going to have a poinsettia shortage,” I tell Ordaz as he walks me through an expansive greenhouse whose tables support a sea of the festive plant’s pointy, dark green leaves. Once the poinsettias move out, young hemp plants will take their place. Next year, Ordaz anticipates shifting the entire operation to hemp—a prospect far too exciting for him to worry over who will supply hardware stores with their 2020 holiday blooms.

Ordaz, like most of this year’s growers, is cultivating plants for CBD. These growers are building off lessons learned in the marijuana business, not least of which is the importance of feminized seed. Cannabinoids, like CBD, concentrate in the flowers, produced only by female plants. If a grower buys seed that produces too many males (or clones that turn out to be male), pulling the plants becomes a labor problem. And it might lead to a crop with lower CBD levels. Since the going price for hemp is directly tied to the percentage of CBD, that matters.

As says Lewis of the NMDA, “Returns are good now, but so is the risk.” On top of noncompliant fields, he says, some growers “have walked away because they couldn’t keep up with the weeds.”

Raising Hemp

No one quite agrees on hemp’s water needs, but the plants mature more quickly than alfalfa, so the water used per acre harvested is likely less. Hemp is highly absorbent—hence its value for phytoremediation—so it needs good soil. (The team at Atrisco Valley Farm talks my ear off about mineralizing, the importance of providing plants with a full mineral diet instead of the nitrogen-heavy inputs common in industrial farming.) As a “new” crop, the EPA has not yet registered any pesticides or herbicides specifically for use on hemp, so weeds and insects have to be managed primarily organically. At Atrisco Valley Farm, some plants were assaulted by tiny red mites. For Ordaz’s partner-farmers, it was worms, cucumber beetles, and leafhoppers.

“There were times I had twenty-five people out there, trimming flowers,” says J.J. Griego, who raised six acres of plants purchased from Ordaz. “I had people out there looking at our field every day.” The day we speak, he’s finalizing the harvest, and says their loss was only twenty-five percent. The state average is upwards of fifty percent. “Just to take it out of the field,” Griego tells me, “you need ten to twelve people.” Because of the labor, it can cost from six to ten dollars a pound just to harvest. (This might be why, when I began researching this article, the internet targeted me with ads for a machine best described as a monster hemp harvester.)

“A lot of farmers aren’t prepared,” says Jae Sanders of Grow the Hemp Shed, who organized a summer workshop series on hemp farming in New Mexico and is working to build a Northern New Mexico Hemp Processors Co-op. “It’s such a different crop than alfalfa.” In addition to the intensive labor costs, Sanders notes some farmers don’t have the indoor room needed to dry the plants prior to sale—much less space to store it if they want to wait out for a better price in a potentially glutted market.

Atrisco Valley Farm. Photos by Stephanie Cameron.

Griego agrees that the market at harvest time is cut-throat. Because of the crop’s sudden abundance, he says, large buyers are coming in to try to buy up biomass at twenty dollars per pound, half the going market rate. He conjectures that some farmers will say yes to that price just to cover the cost of getting their crops out of the ground.

“We get calls every single day wanting us to process other farmers’ stuff,” says Bob Boylan of Roadrunner CBD, one of just nine processors and manufacturers licensed in New Mexico as of October. Boylan, who is also licensed to grow, suggests that manufacturing is inaccessible to most farmers. He adds that when the New Mexico Environment Department (NMED) released rules on processing and distribution in August, he had to spend seven thousand dollars printing new labels. And most processors, Boylan says, ask for deposits upwards of ten thousand dollars. “So a small family farmer can’t necessarily bring their product to market.”

Trials and Assays (The Path to CBD)

“I need a bigger office,” says Johnathan Gerhardt, manager of food and hemp programs at the NMED. “My floor is covered in applications.”

Fifteen, to be exact—and so far, Gerhardt tells me, none have been turned down. Contrary to some of the growers I’ve talked with, Gerhardt doesn’t see the regulation of hemp as being any different from the regulation of any other food product. On the one hand, this is difficult to parse. On top of licensing fees and recall plans, the Hemp Emergency Rule requires product labels to list THC and CBD content in milligrams; even coffee roasters don’t have to quantify the caffeine in a pound of beans. On the other hand, it’s spurious to compare hemp to a food crop like onions or corn.

“Testing is really important,” says Richins. The rules established by the NMED, “That’s really needed. So many oils tested way under what the labels said. People need to trust that the product they’re purchasing has the CBD it says it does.”

Growers are not mandated to test the CBD content in their crops, but most do. To sell “smokable flower”—a market that’s generating a lot of buzz among growers—they need a batch that tests at twelve percent CBD or higher. A testing center like Rio Grande Analytics can also break down the terpenes, which are responsible for the plant’s aroma. “Terpenes and cannabinoids kinda work together,” says Richins. “That’s why you see a lot of full-spectrum oils . . . of course, pharma works the opposite way.”

“It’s more synergistic,” Lori Boylan tells me, contrasting their fullspectrum products to CBD isolates. We’re standing in the spotless trailer where Roadrunner CBD products are manufactured, talking about their process of extracting hemp oil, breathing in the scent of disinfectant. Boylan’s blue eyes play with the light in her blue tortoiseshell glasses while she explains how the flowers are pressed—a form of extraction that, unlike many industrial-scale operations, involves no chemical solvents.

I watch from the sidelines while Boylan and her manufacturing technician heat cold-pressed hemp seed oil in a silver bowl. When it’s just warm, he releases the thick, rich brown hemp oil from a syringe, and it ribbons like molasses into the bowl. Once they mix in the base for their muscle gel—a blend of essential oils and capsaicin—the mixture transforms into something like an Orange Julius. Then they put it into bottles, weighing each one to measure the quantity of CBD.

It’s a remarkably simple process. This is one reason most hemp in New Mexico is being grown for CBD. There’s also building consumer demand for CBD products, and the fact that hemp grown for CBD is more lucrative than hemp grown for fiber.

But how much CBD can the market bear? And how much CBD do we need?

When I talk with Gemma Ra’Star of Wumaniti Earth Native Sanctuary, she’s just finished negotiating with Cid’s Market in Taos to get her products back onto the shelves. She says Cid’s is getting calls from fifty companies a week, all vying to sell the store their CBD products. However, with major drug stores and big box stores just starting to carry CBD products, the market is young. The Brightfield Group, a market research firm focused on cannabis, predicts that the hemp-derived CBD market in the US will top $23 billion in revenue by 2023.

FELLOWSHIP

Everyone feels obligated to point out that you can’t get high off hemp, but thrill is a common note in the voices of the people I’ve talked to. They’re riding the natural high of diving into unknown— and formerly taboo—territory. The risks may be stressful, and there is apprehension about the future, the possibility of conglomeration, the small guys getting squeezed out in a pattern that has come, in late capitalism, to seem inevitable, but for now, a spirit of collaboration pervades the industry.

“It’s really important that people team up,” says Ra’Star. Despite her concern about the CBD craze, she believes the crop has a lot of potential for farmers, and she emphasizes Wumaniti’s support of local growers. “We’re here to help grow New Mexico strong and we’re here to help sustainability,” Ra’Star says.

“Yes, yes, yes,” says Jane Pinto, cofounder of Santa Fe–based First Crop, which contracted with farmers in Abiquiu to grow one hundred fifty acres of hemp that will be processed in the San Luis Valley. First Crop has plans that extend beyond New Mexico (and beyond CBD), but Pinto assures me that the company is committed to staying anchored in New Mexico, to supporting New Mexico farmers, to being known as a New Mexico company and holding corporate and ecological responsibility to the state. “Farmers are teaching us,” Pinto says. “It’s a partnership,” and “the long view is that we will have profitsharing with the farmers.”

The Future

Where is this crop going? Will research uphold or undo faith in the healing powers of CBD? Will pharmaceutical companies isolate other cannabinoids, and patent new medications containing those compounds? How will formal USDA regulations—still being finalized at the time of writing—impact growers in New Mexico? Will states ban smokable flowers? Or will smokable hemp become the next better alternative to vape pipes and tobacco? Not least, will billionaires swoop in and take over, pushing out New Mexico’s smaller farmers and producers?

Atrisco Valley Farm. Photos by Stephanie Cameron.

The answers are still unfolding. But many hope to see local cultivation of the plant variety most familiar as industrial hemp: tall, fiberheavy, densely planted, loaded with seed. Low in CBD as in THC, this is the true hemp of many uses.

“I think people need to lean toward making building materials, making plastics, making fuel,” Ra’Star says. Valdez, at Rezolana Farms, has experimented with making adobe bricks with hemp fiber, and envisions a cottage industry for hemp adobe for sustainable housing. At Wumaniti, they’re building a prayer dome with hemp adobe.

Then there’s hemp’s culinary potential. “The leaves have a really great flavor,” says Anne Delling, “kind of like arugula.” Delling and Tracy Rice founded Grow with Hemp to share resources and connect people around processing, especially for food and fiber. The package of hemp hearts (hulled hemp seeds) they send me is the first I’ve received in weeks that contains no plastic whatsoever. They currently source hemp hearts from Colorado, but they’re trying to turn people onto producing locally.

Not having eaten the seeds on their own, I’m skeptical when Rice tells me she carries hemp hearts in her purse. Then I find myself sprinkling them on ice cream, snacking on them raw, and wondering if I’ll drag myself away from my desk long enough to make anything with them before I’ve devoured the entire package. (The answer is yes, but only because they sent me a ten-minute recipe.) I wouldn’t call eating hemp a spiritual experience, but the hemp cacao bites I made are damn good—like little spheres of flourless chocolate cake. And while the first round of CBD-centric questions are still being answered, I don’t think it’s too soon to ask not what hemp can’t do, but what else are we going to do with it?

riograndeanalytics.net

growwithhemp.com

facebook.com/TheHempShed

freshgrownsystems.com

facebook.com/Atrisco-Valley-Farm

roadrunnercbd.com

certified.naturallygrown.org/producers/4672

Edible celebrates New Mexico's food culture, season by season. We believe that knowing where our food comes from is a powerful thing. With our high-quality, aesthetically pleasing and informative publication, we inspire readers to support and celebrate the growers, producers, chefs, beverage and food artisans, and other food professionals in our community.