Learning from the Keg to the Grain

By Briana Olson

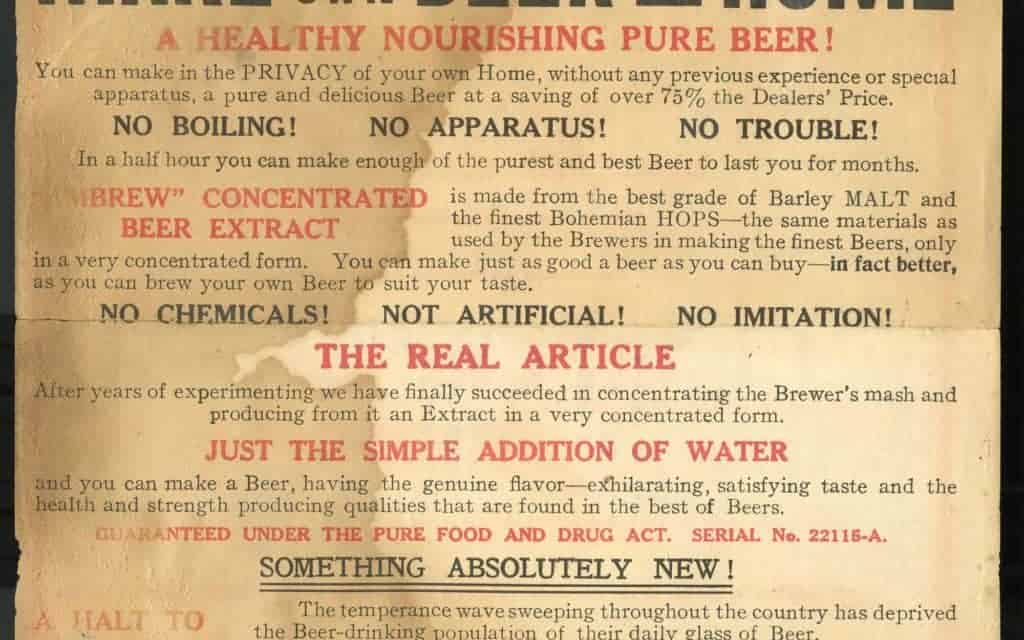

Make Your Own Beer at Home, Advertisement for malt extract, circa 1900. Courtesy of the Warshaw Collection of Business, National Museum of American History Archives Center.

“Would you like a taste?” asks homebrewer Shawn Crawford, holding out a plastic measuring cup filled with chocolate-colored liquid. It’s Learn to Homebrew Day (yes, that’s official), and I’m at the Rio Bravo Brewery, where local homebrew clubs the Worthogs and the Dukes of Ale are hosting a demo to introduce craft-beer drinkers to the hobby of brewing beer. At 10am on an overcast Saturday, most of the tables are empty (the brewery is not yet serving), but none of that dampens the enthusiasm of the dozen homebrewers who’ve set up on Rio Bravo’s patio. Awash in technical terms and pictures of chemical bonds and chains, I’ve jotted down things like “vorlauf,” “alpha-amylase,” and “isoamyl acetate,” and I’m not sure if “whirlpooling” refers to a step in the brewing process or my current frame of mind. A taste? That I can do.

What I taste is earthy and slightly sweet, almost closer in profile to a condensed vegetable broth than to the amber ale the Crawfords will be enjoying over the holidays. They’re currently preparing to rinse the mash to extract all the sugars from the grains—a process known as sparging that follows the mash and results in wort, or unfermented beer, which I’ve just sampled. Like most of the brewers here today, they’re using the all-grain method, in which malted barley grains are soaked in hot water so that their starches will (with the help of enzymes like alpha- and beta-amylase) break down into fermentable sugars. Beginning brewers usually skip this step—some homebrewers are content to use the simpler, cleaner extract method for years—but most will eventually decide that they want to start their beer from scratch.

“Anyone can do this,” insists brewer Troy Satterthwait. “All you really need is a pot and a bucket.” Satterthwait likes to build, and the system he’s using is a touch more elaborate. He’s soaking malts in a cooler fitted with a strainer and a spigot and perched on the broad shelf he built into a short ladder. In a few minutes, he’ll use gravity to strain the sugary wort into a steel pot below. He’s rigged the burner from a turkey roasting kit to use for the boil—the next step of brewing, where the wort is boiled and hops added—and his ingenuity reinforces his point. Anyone can do this.

A few days later, when I stop by local homebrew supply shop Southwest Grape & Grain, owner Donovan Lane echoes this refrain as he cracks open one of the recipe kits he recommends to first-time brewers. Lane explains how much these kits have improved over the years, telling me how his first homebrewing experience was so boring that he switched to the all-grain method on his second try. (He ended up with a decent beer, as well as a tremendous mess—he recommends that beginners stick with extract for at least a few batches.) Now, the typical kit contains a recipe and ingredients for brewing a particular style—having somehow pegged my preferences, Lane is showing me the kit for a Belgian IPA—using the extract method. Most kits include a mesh bag of specialty malts to steep in the wort, adding more art to the process, as well as yeast, seasonings like citrus peels and coriander, and, of course, hops.

Hops tend to garner more attention than malts when it comes to marketing craft beer, but malts turn out to be the more essential of the two. In fact, before the advent of the German Purity Law some five hundred years ago, most brewers used a blend of botanicals known as gruit to impart character to their ales. The original law, enacted as much out of market concerns as out of the desire to regulate production of safer, high-quality beer, stipulated that only three ingredients could be used in making beer: water, barley, and hops. (Yeast, according to several brewers I’ve spoken with, was inadvertently carried into the wort on wooden spoons until its official discovery in the nineteenth century.) Knowing the importance of malts abstractly—understanding that, as one homebrewer put it, yeast has to eat sugar before it can poop out alcohol and CO2—is different from standing in the grain room at Lane’s shop after a crash course in the role enzymes play in producing that sugar.

The room smells faintly grassy, warm and dry, and there’s something about the familiar, elemental quality of grain that appeals to me. Lane points out the bins of base malts—those whose sugar-producing role will influence a beer’s body, taste, and alcohol content—and invites me to sample some of the specialty grains that brewers rely on to refine color and flavor. Raising malting barley is not easy, and the business of converting that barley into malt is still dominated by a handful of global companies, but there’s a movement afoot to localize both growing and malting (with Alamosa’s Colorado Malting Company and Taos Mesa Brewing being the two nearest examples). And experiencing the textures, flavors, and scents of these grains brings me a satisfying step closer to grasping what goes into the making of local pilsners and IPAs.

This might be why I’m not surprised when Lane tells me some customers brew because they want to know what’s in their beer. We’re standing behind plastic buckets and carboys and gleaming steel fermenters, a row of coolers filled with yeast and packets of hop pellets off to our right, and I’ve asked him, given the plethora of craft beers now available, why learn to homebrew? He explains how the demographics of homebrewers have changed over the years. It used to be people who wanted to save money, or who wanted to try hard-to-find craft styles. Now, he says, it’s more about the hobby. For some, it’s knowing the ingredients—whether that means knowing their beer wasn’t brewed with the rice flakes used in cheap commercial lagers, being able to brew gluten-free, or understanding that an acidulated malt will lend sour notes to a farmhouse ale. For others, Lane says, it’s about experimentation. And for all homebrewers, it’s about participating in the process and having the pleasure of filling a glass and saying, “I made that.”

Left: Donovan Lane at his Albuquerque homebrew shop, Southwest Grape & Grain. Right: Homebrewer Laurie Goodale-Slusher with her all-in-one, all-grain electric brewing system. Photos by Briana Olson.

This might be why I’m not surprised when Lane tells me some customers brew because they want to know what’s in their beer. We’re standing behind plastic buckets and carboys and gleaming steel fermenters, a row of coolers filled with yeast and packets of hop pellets off to our right, and I’ve asked him, given the plethora of craft beers now available, why learn to homebrew? He explains how the demographics of homebrewers have changed over the years. It used to be people who wanted to save money, or who wanted to try hard-to-find craft styles. Now, he says, it’s more about the hobby. For some, it’s knowing the ingredients—whether that means knowing their beer wasn’t brewed with the rice flakes used in cheap commercial lagers, being able to brew gluten-free, or understanding that an acidulated malt will lend sour notes to a farmhouse ale. For others, Lane says, it’s about experimentation. And for all homebrewers, it’s about participating in the process and having the pleasure of filling a glass and saying, “I made that.”

Back at the demo, Worthogs vice president Chris Teller, who started brewing with a turkey pot while he was in college, has a straightforward explanation for getting into the hobby. “I just wanted to drink beer,” he laughs, adding, “it probably wasn’t very good.” He’s since graduated to a single-tier steel system with enough hoses and pumps to intimidate anyone new to the process, and today at Rio Bravo he’s teamed with Ben Cryder, who revels in the chemistry of brewing. “It’s fun to geek out,” Cryder says after rattling off a mini-lecture about the role chemical compounds like esters play in creating (or ruining) the characteristic “funk” of saison. On the other side of the patio, Dukes of Ale member Laurie Goodale-Slusher says with a name like Goodale, she was destined to brew her own beer. But unlike many homebrewers, she did not follow her love of beer to the hobby. As a member of the Society for Creative Anachronism, she started off brewing mead, then figured shifting to beer was a natural transition.

“What I love,” Goodale-Slusher says about being part of a homebrew club and participating in events like this one, “is that you’ll see a million systems—and a lot of times you’ll taste a million great beers.” I think about this while I wander the patio, as impressed with the creativity behind each system as with the variety in styles and recipes. Some things all the brewers I talk with seem to agree on. Foremost, sanitize everything. Use purified or distilled water. Regulate temperatures every step of the way. Add bittering hops early in the boil. Cool wort quickly before pitching the yeast. But whether to build a triple-tier system or brew in a bag or buy an all-in-one electric system; whether to use a smack pack or heat liquid yeast in a flask; whether to add fruits and spices before or after fermentation—these are questions everyone has a different answer for. Brewing, notes Jens Deichmann of Victor’s Home Brew in Albuquerque, can be as simple or complicated as you make it.

Worthogs member Shawn Wright tells me his Balloon Glow Lager was such a hit with out-of-town guests that he now rebrews it annually. Others say they vary recipes and styles almost constantly. Some experiments (like Teller and Cryder’s plans to add prickly pear and green chile to their Belgian saison) involve playing with variables in a classic recipe, while others fall more squarely in the science experiment category. Kirk Bigger, a Dukes of Ale member who admits that he switched to all-grain brewing only after being shamed (and then mentored) by a professional brewer, describes his adventure with brewing a sour during a retreat at the Christ in the Desert monastery. Bigger says he let his sour wort ferment for four weeks—twice the ten- to fourteen-days needed to ferment classic ales like the Belgian tripel he’s brewing today.

Left: Chris Teller and Ben Cryder brew a Belgian saison with Teller’s single-tier system. Right: Troy Satterthwait begins the sparging process with his home-built, triple-tier system. Photos by Briana Olson.

“Patience is key,” says Goodale-Slusher, working nearby. Sometimes new brewers, she adds, don’t want to wait. We’ve been talking about how she’ll minimize exposure to light and oxygen during the secondary fermentation of the pilsner she’s making, and she’s referring to the importance of letting a beer ferment completely, but it occurs to me that experiencing the slow time of the brewing process might be equally crucial. In a culture of hurry, slowness can allow for creating deeper connections to the world around us. For Goodale-Slusher, that means connecting not just to the ingredients, but to the history of the process. She explains how pilsners, like all lagers, ferment at cooler temperatures than ales, and how their second round of fermentation, known as lagering, originated in German caves, where beers would rest at forty degrees, in low light, for several months, leading to a crisp, clear, malty profile.

Eventually, today’s IPA and pilsner and saison brewers begin to tear down their systems, and observers gather at Tad Ashlock’s table, where he’s starting the much quicker process of brewing mead. Dukes of Ale vice president Scott Carpenter is excitedly telling me that come December, his club will be meeting at Broken Trail Spirits + Brew, where members can pick up bottles of the Irish whiskey the brewery/distillery made using the club’s Irish Stout recipe. This is just one of many stories I’ve heard about the two clubs collaborating with local breweries. Waiting, I realize, also creates opportunities to cultivate community.

This morning, I pulled into Rio Bravo’s parking lot wondering if I’d find homebrewers with aspirations to brew professionally. At least a handful of New Mexico’s master brewers got their start in garages or porches, and in today’s gig economy, isn’t everyone scrambling to turn their hobbies into cash? But only one brewer, down from Farmington, shared his hope to open a brewery. What I’ve found instead is how willing pro brewers are to mentor, how much homebrewers love to teach, and how Albuquerque’s two homebrew shops—through monthly classes, annual Big Brew Days, and old-fashioned customer service—build community.

Like Shawn and Maureen Crawford, who have no plans to quit their day jobs in the healing professions, most brewers I’ve met today have no desire to turn brewing into a job. In Goodale-Slusher’s words, “This is my love; this is my zen time.”

Worthogs Homebrew Club

www.worthogshc.com

Dukes of Ale

www.dukesofale.com

Victor’s Home Brew

www.victorshomebrew.com

Southwest Grape and Grain

www.swgrapeandgrain.com

Edible celebrates New Mexico's food culture, season by season. We believe that knowing where our food comes from is a powerful thing. With our high-quality, aesthetically pleasing and informative publication, we inspire readers to support and celebrate the growers, producers, chefs, beverage and food artisans, and other food professionals in our community.