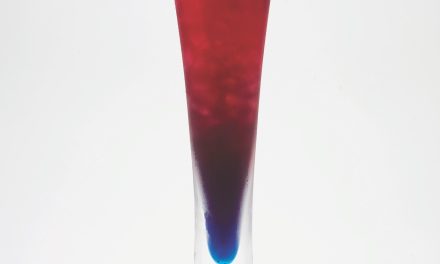

Photo by Calum Lewis

How do you take your honey? Drizzled over a slice of toasted artisan bread slathered with butter? Squeezed into a cup of your favorite hot tea? Baked into cinnamon sweet bread with cream cheese icing? Or just straight up off the spoon? Regardless of how you like it, know that every drop is a precious gift from a tiny bee with only a five to seven-week lifespan. To produce a single pound of finished honey, some 20,000 bees have actively gathered nectar and converted it into honey one-twelfth of a teaspoon at a time for their entire short lives.

Honey is the product produced by bees we think of most often, worth some 150-200 million dollars a year, which pales in comparison to the tens of billions of dollars bee pollination is worth to agriculture. The overall reduction of beehives domestically due to a number of factors including colony collapse disorder only makes honey that much more precious. In fact, the average retail price of honey has almost more than doubled in the past ten years from a little over $3.80 per pound to almost $7.50 per pound.

So what do you have to know about honey that you might not know already? We all know it’s sweet (though not as sweet as sugar) and that in addition to its food and beverage uses, honey is found in everything from cosmetics to medicines. You may also know it comes in various forms (liquid, comb, and creamed) and that a spoonful can help a cough or a cold. So, here are a few other things to know about honey (and honey bees):

Honey is a highly local product based entirely on the food sources available to bees. Live in an area known for apples? Your local honey flavor will reflect that. Clover, heather, acacia, orange blossom, blueberry, and others are common honey varieties found both at farmers’ markets and at the grocers. Some areas are better known for a particular variety than others such as orange in Florida, blueberry in the northeast, or buckwheat and clover in the upper Midwest.

Producers – taking into account seasons and the expected use, blend different honey to arrive at a particular flavor profile. Beyond the sweetness of honey, and they are noticeably different when it comes to sweetness, the flavor profile is what most consumers hone in on. And while sweetness and flavor are best evaluated by tasting them alone we rarely eat honey that way. Honey that is particularly good in beverages like tea will probably be lighter and a touch sweeter than others.

“Raw” honey has no official definition but it is generally understood by consumers to mean that a honey has not been filtered or overly heated. Filtering is done to remove impurities, including pollen, from the honey during processing and in order to be filtered, honey must be warmed. Micronutrients and minerals are not affected by either process according to the National Honey Board. Blending honey also requires heating. But like anything else in the world of food, heating changes the flavor especially if it is overheated. Honey that is minimally processed prior to bottling is more desirable than a highly processed product that really is just no more than liquid sugar.

Knowing the honey producer, as well as looking for and trying a variety of honey for flavor and sweetness, is an important part of the relationship between consumer and producer. Most apiarists are generous with tastings and samples wherever you find them. Take them up on their offer to try different kinds of honey and consider what you will be using the honey with when purchasing. There really are types that are better with tea or fresh fruit, baked into a dessert, or spooned over toast. Try them all.

And finally – do what you can to help preserve and protect pollinators of all types, and especially the domestic honeybee. At its simplest, just purchasing local honey at the farmers’ market can do this. It’s the whole “use it to preserve it” idea. If there is a strong market, producers will continue to produce honey and taking steps to protect honeybees is in their best interest. Planting flowers, bushes and trees that attract pollinators is another very simple way to protect honeybees and pollinators in general. And supporting and participating in local, regional and national pollinator organizations, such as a local beekeeping organization or the Xerces Society is a great way to stay connected and involved in the preservation of honeybees and other pollinators.

Honey gathering for consumption is over 8,000 years old and probably dates to the earliest times of man. Honey, and the vitally important pollination that goes along with it, can certainly last another 8,000 years as long as consumers keep in mind all of that work – a twelfth of a teaspoon at a time, that went into sweetening your hot cup of tea.

Substituting local honey for sugar in recipes:

There are fours things to remember if you are substituting honey for sugar in a recipe – aside from the flavor difference between the two:

Since honey is sweeter than sugar we need to use less; substitute 1/2 to 2/3 of a cup for each cup of sugar. The reason for the range of 1/2 to 2/3 is that some honey is sweeter than others! Clover or Acacia honey is sweeter (so use 1/2 cup) than Chestnut or Dark (use 2/3).

Honey is obviously more ‘liquid’ than sugar so we must reduce the other liquids in a recipe by 1/4 cup per cup of liquid (you can total up all the liquids and reduce by 25%).

Honey is acidic so we need to balance this by adding 1/4 teaspoon of baking soda to the recipe for each cup of honey.

Honey caramelizes or ‘browns’ quicker than sugar, so reduce the oven temperature by 25 F° and check the item regularly to prevent over-browning or burning.

Edible celebrates New Mexico's food culture, season by season. We believe that knowing where our food comes from is a powerful thing. With our high-quality, aesthetically pleasing and informative publication, we inspire readers to support and celebrate the growers, producers, chefs, beverage and food artisans, and other food professionals in our community.