Exploring a Growing Food Basin at the Top of the Watershed

by Willy Carleton

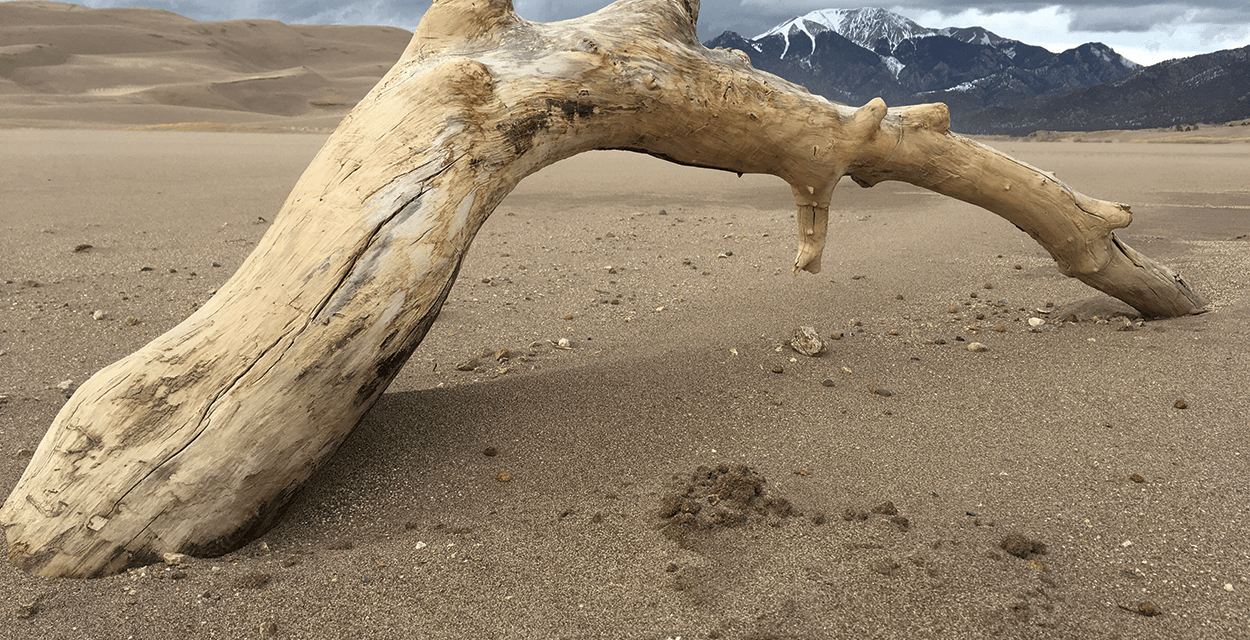

We set out for the San Luis Valley of Colorado, following the path of the long-gone Chili Line railway, in search of some warm waters, seed potatoes, and a few good meals. Entering the valley, my friend Josh and I were greeted with expansive scenes of flat farm fields, dotted with center-pivot irrigation equipment and large potato harvesters, stretching in all directions to distant white-capped peaks. The valley, which up until half a million years ago contained a massive lake, forms a partial basin characterized by dramatic juxtapositions of industrial agriculture, grasslands, mountains, hot springs, and even the Sahara-like sands of the Great Sand Dunes National Park.

Over the course of a February weekend exploring the San Luis Valley, we discovered that it is not only a geologic wonder, but a humble culinary wonder as well. We stumbled upon few fancy, high-priced restaurants advertising farm-to-table credentials, but we also found many small, relatively inexpensive establishments that featured delicious local food options. Accessibility, more than pushing the boundaries of culinary creative expression, seem to drive the philosophy surrounding local food. With its base of industrial agriculture focusing on potatoes, alfalfa, and wheat, as well as a growing number of small, diversified market farmers, the valley has begun to develop a local food system that incorporates producers of various scales to keep a sizable portion of locally-raised products in the valley and provide healthier food at affordable prices. Just as the partial basin retains much of its water, the San Luis Valley has taken steps to retain much of the food it produces.

One reason for the growth of the San Luis Valley’s local food system is the San Luis Valley Local Foods Coalition. Started in 2008, the non-profit coalition runs several programs, such as the Valley Roots Food Hub that coordinates food sales and distribution between local farms and local buyers; cooking classes in both English and Spanish that emphasize healthy, local ingredients; a local food guide with lists and maps of local producers; and the establishment of a Rio Grande Farm Park in Alamosa. Yet the coalition would not work if it were not for the growers that populate the valley, raising a diversity of products at varying scales.

As a first stop in our culinary tour, we’d arranged to meet with one of these farmers, Ernie New of White Mountain Farm. We found New at the Pit Stop, a tiny gas station and convenience store in Mosca, Colorado, where he has his office. Sporting jeans, a tucked-in plaid shirt, a baseball cap with the US presidential seal, and heavy-duty orthopedic sneakers, the seventy-four-year-old farmer greeted us with a firm handshake and wry grin. “What can I help you with?” he asked as he pointed us to our chairs.

Chances are good that if you have bought a local, organic potato from La Montañita Co-op anytime in recent years, you have tasted a product from one of New’s large, center-pivot irrigated fields. Like many growers in the region, White Mountain has relied on potatoes, which are well-suited for the valley’s isolation and short growing season. Yet, unlike other farmers in the valley, New has also worked hard over roughly three decades to introduce an entirely new staple of the Andes to southern Colorado and to the rest of the country—quinoa. A third-generation organic farmer in the valley with an eye on the future, New is one of the first large-scale quinoa growers in the country, and remains one of the few growers to successfully raise a commercial crop. I asked him how he started with quinoa and why quinoa makes sense as a crop for the San Luis Valley.

Top left, clockwise: The taps of Three Barrel Brewing (photo courtesy of Three Barrel Brewing); the newly opened Crestone Brewing Co. (photo by Willy Carleton); Three Barrel Brewing Co. (photo courtesy of Three Barrel Brewing); one of three pools at Joyful Journey Hot Springs and Spa; and White Mountain Farms’ quinoa (photo by Willy Carleton).

“When we got started with quinoa, we didn’t know how to grow it, how to clean it, or how to cook it. Nothing,” New reminisced. “We had to learn it all from scratch.” He explained that his relationship with quinoa began in 1984, when Dave Cusack, an idealist with a PhD in history whose father had raised potatoes in the San Luis Valley, approached him about growing organic quinoa. Cusack, along with two partners, had brought a small amount of quinoa from Bolivian and Chilean markets several years earlier. He had grown a handful of seed two years prior, but remnant herbicide residue in the field doomed the crop. (In an incredibly sad and mysterious turn of events, shortly after his meeting with New, Cusack was shot in the back near some ruins outside of La Paz. Though declared by local police to be a victim of a botched robbery, theories remain, as The Atlantic reported in 2010, that Cusack’s leftist goals of helping empower Bolivian farmers by developing a market for quinoa may explain the tragic murder.)

In his first foray with the grain, New grew out “Dave’s 407,” seed named after the slain idealist, on thirty acres. The crop did well in the organic fields, and Ernie added it into his rotations with potatoes and alfalfa. In 1987, he helped found White Mountain Farm and thus began his thirty-year breeding project to adapt seed to the climate of the San Luis Valley. New explained that he has worked with over two hundred strains of quinoa on a one-acre research plot and has developed several new varieties, including a “black quinoa” that New believes is a mix of quinoa and local chenopod (Lamb’s quarters) varieties.

Quinoa has proven a tricky crop for White Mountain Farm over the years, but New has remained convinced of its potential benefits for his farm and for others in the valley. One obvious incentive to continue experimenting with the crop is the growing market for the grain. “There’s a wide open market for it,” New explained as he rattled off orders, large and small, from all parts of the country and globe. Most of the orders, he explained, he simply cannot fill. Another prime reason to focus on quinoa is the crop’s relatively low water needs. Requiring much less water than potatoes or alfalfa, quinoa has gained attention from other farmers throughout the valley. “We need a crop that takes less water,” New explained, “so a lot of people are wanting to go the quinoa route.” Quinoa production is on the rise in the valley, according to New. Currently, New raises about one hundred thirty acres of quinoa annually, and he works with eight neighboring farmers who produce an additional two hundred seventy acres per year, on average.

The easiest way to find White Mountain Farm’s quinoa is to either order it online or stop by the Pit Stop, where you can purchase it in one-, five-, or twenty-five pound bags. And, as I was soon to learn, the unique locally grown grain is prevalent in restaurants and breweries throughout the valley. I opted for a five-pound bag, along with a few larger bags of organic seed potatoes for my garden at home, and thanked the long-time farmer for his time and the many grains of thought he had planted in my head.

After leaving Mosca, and taking a quick detour to scramble up the rolling slopes of sand towering on the town’s horizon, we continued north to the small community of Crestone in quest of a good dinner. Perched at the base of the Sangre de Cristos and overlooking the vastness of the valley floor, this small but thriving former mining town supports several spiritual retreat centers, galleries, a community center, and a food co-op well-stocked with locally produced organic vegetables, meats, and dairy products. A leisurely walk across the entirety of the town takes approximately two minutes, so it didn’t take long to settle on the best, and only, food option we could find: the newly opened Crestone Brewing Co.

Locavores restaurant in Alamosa. Photos by Willy Carleton.

The brewery, which opened as a taproom in May and started brewing this past October, offers a wide variety of beer and locally sourced barroom fare including french fries from local potatoes, burgers from local beef and yak, local lettuce from Brightwater Farms in Monte Vista, and, of course, a side of White Mountain Farms quinoa. The warm atmosphere, hearty food, complex beer, and homemade kombucha make the brewery a great place to refuel after spending a few hours exploring the sweeping, windy dunes.

We hung our hats that night at the Joyful Journey Hot Springs, which contains three pools of geothermic waters to soak in and offers rooms in its main lodge, as well as private yurts, tipis, and camping sites. Soaking in any of the resort’s three pools is a great way to finish off a day of exploring the valley, and the rooms (we opted for a yurt) provide all you need for a restful sleep. If you stay the night, however, you might consider skipping the complimentary continental breakfast. The food at the 4th Street Diner and Bakery in the nearby town of Saguache is well worth the short drive.

4th Street Diner and Bakery, which master baker Esther Mae Last opened six years ago, sits along a main street populated with a food co-op, art galleries, two theatres, and a large county courthouse. The restaurant’s building, built in 1892, features a wood floor and ceiling, a plethora of Americana on the walls, and a large wood stove near the center of the dining area. A steady stream of locals poured in for coffee, a hearty home-style breakfast, and good conversation with friends and neighbors.

A waitress approached our table to take our order. “Are any of these dishes made with local ingredients?” I asked. “They’re all local,” she replied with a quizzical smile. She took a kettle off the wood-fired stove and refilled my cup of tea. She quickly, almost impatiently, explained which farms had produced the meat, eggs, chile, and potatoes that made up the bulk of the menu. Her reaction to my question made me wonder if, similar to being in certain parts of France and asking if the local wine is organic, perhaps asking if the potatoes or chile were local was a slight insult. I am, unfortunately, more accustomed to the opposite experience of seeing local farms on a menu, only to ask and learn that few ingredients are actually sourced from those farms on any given day. Whether or not I read the server correctly, I found refreshing the restaurant’s underlying and unpretentious assumption that using primarily locally sourced food was normal and to be expected. I ordered the huevos rancheros, which along with the wood stove and hot tea, warmed me to my bones and set me up for another day of exploring the valley.

Back on the road, we drove toward the headwaters of the Rio Grande in the San Juan Mountains, watching the flatlands of the valley slowly begin to swell and roll. An approaching winter storm eventually sent pockets of low-flying clouds through the grassy hills, revealing only brief glimpses of the scattered trees, black Angus cattle, and old wooden barns that seemed to populate most of the landscape. With a light rain turning into flurries of thick snowflakes, we decided to make the town of Del Norte our furthest destination. Luckily for us, the weekend theme of good food and drink continued as we stumbled across Three Barrel Brewing.

Local ingredients pervade the food menu, and especially the beer list, at the brewery. The brewers rely entirely on San Luis Valley-grown barley, wheat, and rye malt, all from the Colorado Malting Company in Alamosa; honey from Haefeli’s Honey Farm in Del Norte; and, for certain beers, wild hops from Colorado and New Mexico. The brewery is even planning to begin brewing a quinoa beer, based on White Mountain Farms quinoa that the Colorado Malting Company is currently malting.

I noticed distinct signs of New Mexico in the brewery—a Chimayó sour ale, for example, in their Penitente Canyon series—and asked owner Will Kreutzer about New Mexico’s influence on the brewery, and the valley more broadly. “The influence here in the valley from New Mexico is everywhere,” he replied without hesitation. “The San Luis Valley is just an extension of northern New Mexico.” He explained that while some ingredients, such as wild hops, come from New Mexico, the main influence is cultural. He cited a deep camaraderie among brewers in the valley and those in New Mexico: “It’s really an untold brotherhood.”

Before descending from the valley plateau back into New Mexico, we made a final stop at Locavores in Alamosa. Located in what looks like an old bank building near the Walmart, the small sandwich shop started in 2016 by local farmers Matt and Wendi Segar caters squarely to locals. The restaurant applies a fast-food eating experience to a slow-food, ingredient-sourcing philosophy. A large map of the valley, filled with stars that mark the location of ingredient-providing farms, covers the wall to the right as you enter. Whether a gyro, banh mi, Cubano, or cheese steak, nearly every component of the sandwich you order will contain local ingredients, will arrive to you fairly quickly, and will cost somewhere between $7.50 and $12. With house-made sauces and optional sides of fingerling potatoes, the simple sandwiches are packed with flavor and leave little room for hunger. On a small blackboard in the corner of the restaurant, as I meditated on the final bites of my gyro, I noticed words that seemed to articulate the attitude I had encountered throughout my weekend trip: “We think a community that grows most of the region’s food should have access to that good food.” My weekend tour can attest that the restaurant, along with several others in the valley, have taken a small but inspiring stride toward attaining that simple and worthy goal.

White Mountain Farm www.whitemountainfarm.com

Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve

www.nps.gov/grsa

Crestone Brewing Co.www.crestonebrewingco.com

Joyful Journey Hot Springs

www.joyfuljourneyhotsprings.com

4th Street Diner and Bakery www.facebook.com/4thStreetDinerBakery

Three Barrel Brewing www.threebarrelbrew.com

Locavores www.eatlocavores.com

Edible celebrates New Mexico's food culture, season by season. We believe that knowing where our food comes from is a powerful thing. With our high-quality, aesthetically pleasing and informative publication, we inspire readers to support and celebrate the growers, producers, chefs, beverage and food artisans, and other food professionals in our community.