For African American Motorists in Jim Crow America,

the Green Book was their Bible

By Frank Norris

Route 66 was a magical highway. As Nat King Cole crooned in his 1946 hit, Route 66 “winds from Chicago to L.A., more than two thousand miles all the way.” Having a car meant having a freedom machine, and between the 1920s and the 1970s, millions of people took advantage of that freedom by driving down the Mother Road through New Mexico on their way to California.

Not everyone, however, enjoyed the same degree of freedom while traveling along Route 66. White travelers were free to cruise Route 66 and stop at any side-of-the-road motel, steak-dinner restaurant, gas station, or reptile farm they might encounter along the way. But for African Americans, it was not so easy, because the prevalent racial attitudes of mid-twentieth-century America forced them to adapt, to be inventive, and at times to simply endure. The recent motion picture Green Book has educated viewers on the limited choices that African Americans had when it came time to rest, eat, and even get gasoline. Discrimination took place not only in the South but up north, in the Midwest, and even in western states such as New Mexico.

Route 66 was established in 1926, but well before that, thousands of African Americans had begun migrating out of the rural south as part of the Great Migration. Many settled in New York, Chicago, Detroit, and other large northern cities, but considerable numbers also headed west to California. They looked for economic opportunity in the manufacturing and service sectors and hoped to escape the blatant, painful system of discrimination enforced through Jim Crow laws that had been imposed by southern whites since the late nineteenth century. However, for African Americans who were able to escape the South, life in the larger northern and western cities was by no means easy, and discrimination still existed.

On the whole, the country’s public accommodations, with only slight variations between southern and northern states, were hostile to African Americans. George Schuyler, an African American journalist, recalled, “Prior to 1945, the number of hotels, restaurants, motels and such establishments that welcomed Negro patronage outside the south was infinitesimal.” By 1949, “Negro travelers were welcome in not more than six percent of the nation’s better hotels and motels,” and there were “probably fewer than twenty cities in the country where Negroes [were] not completely barred from white-owned restaurants.”

Given that hostility, African Americans survived while traveling by applying a broad range of well-honed strategies. Many families simply drove straight through to their destination, driving all night long if necessary; they packed picnic baskets of food and stopped only to fuel their gas tank or when nature called. Some families stayed with friends along the way. One Albuquerque business owner recalls that, as a child, she overnighted in national park campgrounds while on cross-country trips. Others kept an eye out for the black part of town. Some black travelers went to the downtown train station and asked a train porter where to stay, while others drove down the main street, looking for a black resident. Or they might ask a white passer-by, “Where can we get something to eat?” or “Where can we find a room for the night?”

Different states and cities along Route 66 had varying laws and customs related to African American travelers, a situation that proved confusing. African American scholar Robert Russa Moton described the challenges of travel before World War II: “How a colored man . . . can be expected to know all the intricacies of segregation as he travels in different parts of the country is beyond explanation. The truth of the matter is, he is expected to find out as best he can.” Given the humiliation of train travel (in Jim Crow cars) and bus travel (where African Americans were forced to take a rear seat), driving gave black travelers a considerable degree of flexibility, freedom, and anonymity—a “protective bubble,” as one historian calls it. They also knew, however, that the roadside was not so egalitarian.

For courageous black motorists, travel along Route 66 could be every bit as difficult as it was elsewhere. Irv Logan Jr., a black resident of Springfield, Missouri, said that “between Chicago and Los Angeles you couldn’t rent a room if you were tired after a long drive. You couldn’t sit down in a restaurant or diner or buy a meal no matter how much money you had. You couldn’t find a place to answer the call of nature even with a pocketful of money . . . if you were a person of color traveling on Route 66 in the 1940s and 1950s.” The viewpoint of James Williams, who rode with a group of friends in 1942 from Louisiana to Flagstaff, was just as glum: “You’d have to drive all night and have to look for the colored part of town, maybe you could find a room.” African Americans knew all too well that white hotel owners had a long list of ready-made excuses for refusing accommodations: “We just rented our last room,” “We forgot to turn off the vacancy sign,” and, in at least one documented case, “The rest of the motel owners will ostracize us.”

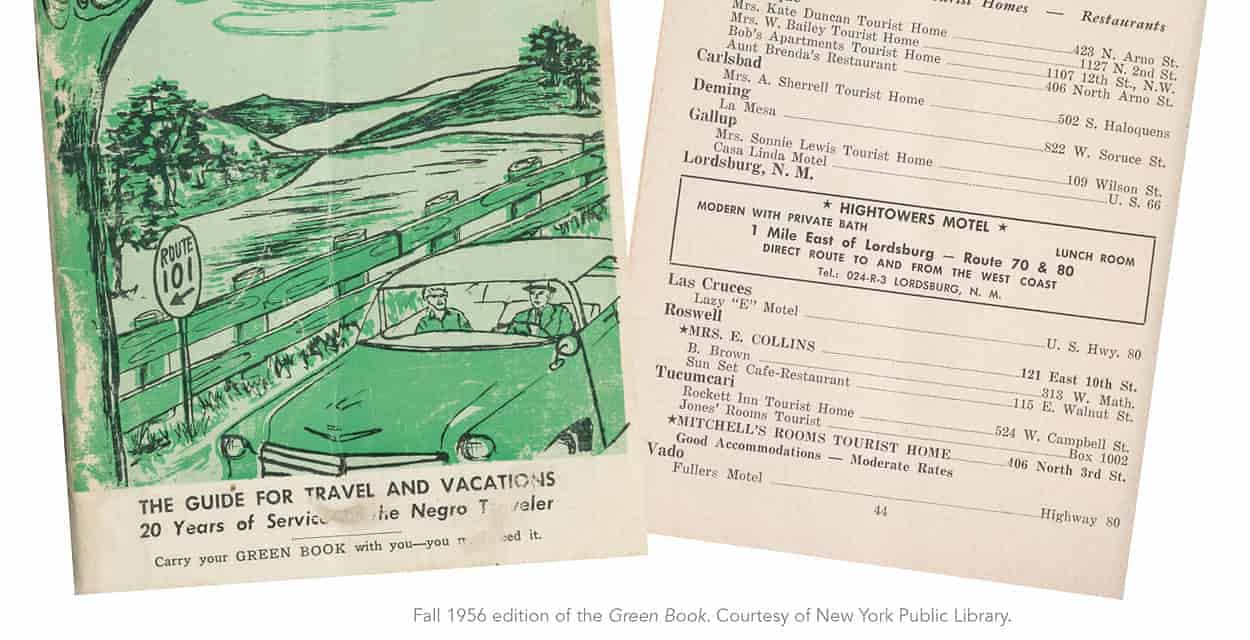

During the late 1920s, when Route 66 was a newly designated highway, black motorists had few ways of knowing which hotels and restaurants would accept them. But in 1936 a new guide for black travelers emerged called the Negro Motorist Green Book. Published by an African American, New York based travel agent Victor Green and his wife Alma Duke Green, the Green Book quickly gained in popularity, and revised editions appeared annually. It offered hotel and restaurant listings for cities throughout the United States, though the majority of its listings were for New York, Chicago, and other northern cities that had large black populations. The Green Book, priced at a dollar or less, was distributed at Standard Oil and Esso stations throughout the country. It provided valuable options for travelers who hoped to avoid “embarrassment” and “inconveniences,” as Green tactfully phrased it. By 1962, some two million copies of the Green Book were distributed to the traveling public. Given the pervasive hostility and uncertainty imposed by white America, it was no wonder that black-owned travel guides were used so widely. The matter-of-fact slogan on the cover of the Greens’ guide testified to its value: “Carry Your Green Book With You; You May Need It.”

Within New Mexico, popular attitudes toward African Americans varied by location. Conditions in southern and eastern New Mexico were similar to those in Texas, while Santa Fe was reputedly more tolerant. Albuquerque was somewhere in between. In 1948, a protest at the local Walgreens forced the management to open its soda fountain to African Americans, but other public facilities refused to accept black patrons. In February 1952, the Albuquerque City Commission passed an ordinance that prohibited discrimination in places of public accommodation and, three years later, the New Mexico legislature passed the first statewide civil rights statute in the Intermountain West. Neither of these laws, however, carried a strong enforcement mechanism. As a result, there was occasional backsliding, such as an incident in October 1960 when an Albuquerque restaurant refused service to a University of New Mexico student from Ceylon (present day Sri Lanka).

In New Mexico, hostelries advertising to African Americans were listed in Tucumcari, Santa Rosa, and Albuquerque. West from there, black motorists who had previously traveled along the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway trusted that they could rely on meals and a warm bed at the various Fred Harvey Houses in New Mexico, Arizona, and California. The Harvey Houses in these states, they knew, did not discriminate against African Americans or other minorities by denying service, and they also refused to maintain “separate but equal” dining facilities.

Other than the Harvey Houses, however, early black travelers had few lodging options between Albuquerque and Los Angeles. Before 1949, neither the Green Book nor any other black travel guide listed hostelries anywhere along the eight hundred miles of road between the two cities. But by the mid-1950s, guidebooks advertised hotels and restaurants catering to African Americans in Gallup, New Mexico; Holbrook, Flagstaff, and Kingman, Arizona; and Needles and Barstow, California.

Still, New Mexico could be unwelcoming. A black resident who lived in Tucumcari during the 1950s noted that a typical black family driving through town “might not have been able to stay” in one of the white-owned motels on the main boulevard. In 1955, an NAACP official published the results of a survey in a local Albuquerque newspaper showing that less than six percent of the Central Avenue motels and tourist courts welcomed African American travelers, and that the city’s larger motels were “consistent in their refusal to accommodate” African Americans. According to one longtime black Albuquerque resident, most black travelers attempting to stay at a Central Avenue motel would have been refused service, while another longtime resident said travelers “could never tell what the reaction might be.”

A survey of the Green Book issues and other black-oriented travel guides has identified three hundred sixty properties along Route 66 between Chicago’s outskirts and the Santa Monica beachfront. A field check of those properties reveals that only about one-third of these hotels and restaurants are still standing. This state of affairs is perhaps not surprising. During the 1950s and 1960s, many of the businesses in traditional black neighborhoods were sacrificed in the name of urban renewal or demolished because of freeway construction. Many of the motels on long-standing commercial strips, moreover, fell by the wayside, unable to compete with similar businesses that catered to the white trade.

Twenty-five known Route 66 businesses in New Mexico catered to black patrons. In Tucumcari, two north-end hostelries advertised in the early black guidebooks. By the early 1950s, Gaynell Avenue (now Tucumcari Boulevard) featured the La Plaza Court, which advertised to black travelers. Shortly afterward two African American entrepreneurs—Nolan Jones and his partner Bob Richards—opened the Amigo Motel and Café at the east end of the motel strip. The nearby village of Santa Rosa historically had few black residents; even so, the Will Rogers Motel, on the south side of Route 66, advertised to black travelers.

Albuquerque offered a fairly broad range of accommodations to African Americans over the years. During the 1920s and 1930s, the Alvarado Hotel—with its Harvey House restaurant—may have been the only hostelry in town that welcomed black travelers. By the late 1940s, the black traveler could choose from two tourist homes, a hotel, a motel, and three restaurants. And by the early 1960s, two more motels, both located on west Central Avenue, catered to an African American clientele. In Gallup, directories from the late 1940s list two tourist homes and two downtown hotels that welcomed black travelers, and by the mid-1950s the Casa Linda Motel was a black-owned facility at the east end of town.

Out of the twenty-five New Mexico businesses that advertised to black travelers before 1964, just six still stand today. In Tucumcari, Mitchell’s Rooms and the Rocket Inn, both residential structures, remain; the La Plaza Court does too, although it has been substantially remodeled in recent years. In Santa Rosa, the Will Rogers Motel is still in business. In Albuquerque, the iconic De Anza Motel on Central Avenue has recently been redeveloped, and in Gallup, a two-story business building once known as the New Commercial Hotel stands near the railroad station. These “safe havens” are symbols of a period in which discrimination in public accommodations was widely practiced. Buildings such as these need to be recognized for their valuable role in providing rest and comfort to black and other nonwhite highway travelers who journeyed along Route 66 between 1926 and the 1964 passage of the Civil Rights Act, which outlawed discrimination based on race, color, religion, or national origin in hotels, motels, restaurants, theaters, and all other public accommodations. Only recently has a larger population begun to recognize the key role that these businesses played in providing safety, comfort, and dignity to early black travelers. As a result, attempts are being made to identify, inventory, and evaluate these motels, tourist homes, restaurants, and similar facilities, as well as to recognize the travelers themselves for their courage and for paving the way for those who came after.

Edible celebrates New Mexico's food culture, season by season. We believe that knowing where our food comes from is a powerful thing. With our high-quality, aesthetically pleasing and informative publication, we inspire readers to support and celebrate the growers, producers, chefs, beverage and food artisans, and other food professionals in our community.