New Mexico Programs Making a Difference

for Future Generations

By Lois Ellen Frank

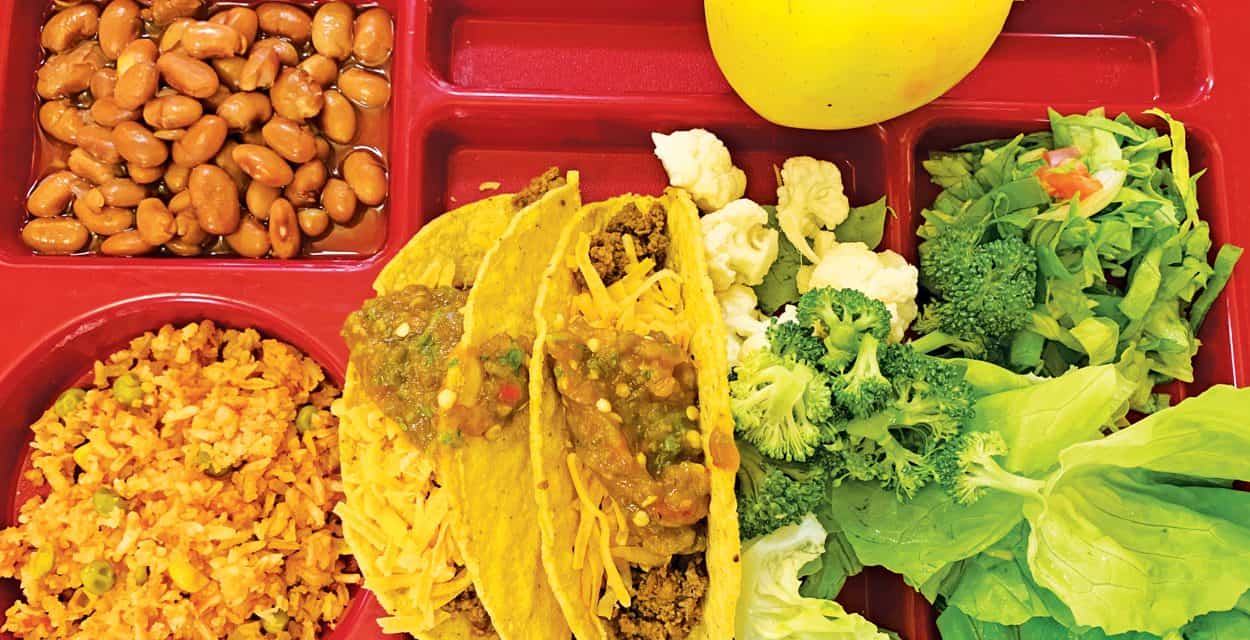

Bernalillo Public Schools cafeteria meal with pinto beans, apple, salsa, tomatoes, onions,

jalapeños, and lettuce, all local. Photo courtesy of New Mexico Public Education Department.

When everyone has access to healthy fruits and vegetables, our culture and our communities are strengthened. When Native communities have more control over the mechanisms and policies of food production and distribution, they can assert their right to healthy and culturally appropriate food and their right to define their own food and agriculture systems. Increasing food sovereignty requires incorporating into our local food policy Traditional Ecological Knowledge, or wisdom of the ancestors that is handed down over generations through traditional songs, stories, and beliefs. Encouraging the continuation of this knowledge is an important element of health and wellness and a crucial step toward food justice, food security, and environmental justice. I am so happy to say that such a shift is well underway in New Mexico, for both Native and non-Native communities, and this is good news for everyone.

Several initiatives across the state are laying important groundwork for increased local food sovereignty, including a food-service training program I am working on in collaboration with the New Mexico Department of Health. The mission of the program is to bring more healthy, indigenous, culturally appropriate foods to seniors in tribal communities through professional development of food service staff. In 2019, my Santa Fe–based catering company, Red Mesa Cuisine, partnered with Siobhan Hancock from the Department of Health’s Obesity, Nutrition and Physical Activity Program (ONAPA), along with the Office of Tribal Liaison, the Aging and Long-Term Services Department, and the Office of Indian Elder Affairs. We held two hands-on trainings in different regions of the state for nearby food service staff from elder centers in tribal communities.

The trainings were an amazing experience. I ran my portion of the culinary trainings alongside Chef Walter Whitewater and Chef Aurora Fernandez, two chefs that work with me at Red Mesa Cuisine. The cooks that participated were divided into small groups at each culinary station, engaging in hands-on food preparation of multiple recipes, followed by a tasting of the foods each group had prepared. Things started off quietly, and then the cooks began to have fun as they worked together.

We introduced new methods of preparation as well as new flavors. In some instances, we presented new ways to cook traditional Native American recipes. For example, when preparing Indian tacos, we used ground turkey and pinto beans and toppings including arugula, radishes, microgreens, and sprouts. The Hominy Harvest stew features locally grown hominy/posole in both blue and white, fresh zucchini and yellow squash, fresh tomatoes, fresh onion, fresh garlic, New Mexico red chile pods and powder, and azafran (Carthamus tinctorius), a native saffron substitute produced in New Mexico. Another delicious contemporary dish we made from ancestral ingredients is the Native American parfait: blue corn mush layered with a berry compote, fresh apples as a sweetener, and a topping of toasted and chopped New Mexico pecans. These recipes, along with the No Fry Frybread (fry bread dough that is grilled instead of fried), were some of the modern twists we introduced to old, familiar recipes.

During these intensive two-day, hands-on trainings, we also incorporated knowledge of the meaning of the foods we worked with. We talked about how foods like corn, beans, and squash—also known as the Three Sisters—play an important part in Native American cuisine and how best to integrate these foods into dishes that can be prepared for elder and senior centers.

Not only was the food delicious, but seeing the creative inspiration ignited among the cooks was the highlight for us during the trainings. And when it came time to close the circle, we had created bonds and relationships through our shared history and love of cooking. We learned, we ate, and we shared our Indigenous knowledge with each other, and that was invaluable to all of us.

In 2020, with COVID-19 pandemic restrictions and social distancing guidelines in effect for the foreseeable future, we transitioned to the development of virtual sessions that will be available early in 2021 for cooks, kitchen managers, and other food service staff at tribal elder centers and senior centers throughout the state. We hope to return to in-person trainings as soon as health restrictions allow.

In addition to the food service training project, ONAPA supports healthy eating and physical activity through the Healthy Kids Healthy Communities program in ten counties and three tribal communities. In tandem, ONAPA promotes farming and edible gardens in homes, schools, and communities, which not only improves access to healthy foods, but increases income for growers and revenue for local economies.

This important work is an integral piece in the much larger puzzle that is our food system. For decades, the food service system has evolved to rely on corporations that benefit from scale and efficiency, trucking industrial produce and prepared and processed foods to institutions across the country. According to a food systems assessment produced by the Crossroads Resource Center, 90 percent of the food eaten in New Mexico is produced elsewhere, which means that New Mexicans spend about $6.5 billion each year on food produced outside the state. For several years, the New Mexico Food & Agriculture Policy Council and other community-based advocates and partners have called for expanding local farming and getting locally grown foods into the kitchens of schools, Head Start programs, and elder centers. When institutions source food locally, farmers gain revenue and the community gains access to seasonal local foods with the best flavor and the most nutrients. This, in turn, changes the palates for kids, who learn to love fresh, flavorful fruits and vegetables because they are sourced at their peak.

Staff at the New Mexico Public Education Department have been doing their part to bring greater resources to healthy and locally sourced food initiatives. Student Success and Wellness Bureau Director Michael Chavez has supported the growth of the agency’s New Mexico Grown Farm to School Program, creating the key position now held by Kendal Chavez. Hired as the new Farm to School Specialist in 2018, Chavez has helped to build out the program, which serves K–12 students through incentivizing the purchase of locally grown fresh fruits and vegetables for meal and snack programs. Funds are allocated through an application process to schools and school districts that operate the National School Lunch Program. Currently, 504 schools within fifty-eight districts, from Albuquerque to Zuni to Truth or Consequences, are purchasing local food through the Farm to School program. This is only 25 percent of schools in New Mexico, but it represents more than 50 percent of kids in the state.

Hominy Harvest stew, photo by Siobhan Hancock. Right: Native American parfait, photo by Lois Ellen Frank.

Together with cross-sector partners throughout the state, the Farm to School program’s goal is to improve communities’ access to nutritious, affordable, locally grown, and culturally significant foods by linking local food production to local needs. In collaboration with the New Mexico Farmers’ Marketing Association, New Mexico State University Cooperative Extension Service, La Montañita Co-op Distribution Center, and farmers across the state, Kendal Chavez helped create a free-to-low-cost, state-vetted certification process for small-scale farmers to sell their produce. She built a collaborative system that is, as she put it, “bottom up as well as top down,” working from “both a bureaucratic and community-based perspective. All initiatives leverage the power of government to deepen the impact of community vision around school food and farm-to-school.”

When initiatives like ONAPA’s Healthy Kids Healthy Community and the Farm to School Program work concurrently to create systems and environmental changes, healthy eating becomes an easy choice.

Zuni Pueblo is an ONAPA Healthy Kids Healthy Community and an especially good example of a success story in a pueblo community. The Pueblo is currently purchasing food from a school-district-run greenhouse and transitioning to buying directly from Zuni growers. The food service professionals at Zuni Public School District want to buy from their local farmers, and with the Farm to School program in place, they have a clear pathway to do so. Once a local farm is certified, they will be able to provide fresh produce to food service staff at Zuni Public Schools as well as the senior center and Zuni Head Start. The farm-to-school certification process also opens up a Zuni garden-to-cafeteria option. Students study and grow local healthy ancestral foods at the garden; using these foods in schools can advance food sovereignty as well as food security and food justice in the Zuni community. This matters—participating students have the opportunity not only to reconnect to tradition, but to take control of where their food comes from.

Shiprock is another community that has successfully implemented this program. The Shiprock Traditional Farms Cooperative is already approved through the Farm to School program and is working toward providing locally grown food for the Central Consolidated School District, which serves the northern part of the Navajo Nation—a region where many residents have to drive an hour or more to reach the nearest supermarket. It’s also a region where much of the arable land lies fallow; the Shiprock Chapter area has 5,800 acres of developed farmland, but fewer than 1,000 of those acres are farmed annually. To help revitalize idle farms, the cooperative recruits and supports participant farmers in all phases of the farming process, from soil preparation to planting to market, with the intent to achieve large-scale production of fresh produce. With support from the Farm to School program, food-safety trainings that are currently only offered in English and Spanish are being translated to Navajo by Shiprock Chapter leadership. “Our hope is to empower Indigenous leaders interested in food safety and food systems work to take the state curriculum and lead trainings in their own communities,” Kendal Chavez explained. “Both are long-term strategies, and may not happen overnight, but are essential to food justice, food sovereignty, and broader food systems work.” Thanks to the appropriation of state funds, her program is helping to build a self-sustaining food system within this community.

Beans, sumac, chicos, atole corn, hominy, fruits and vegetables—the foods grown with love and care in these local farms and gardens also revitalize the connection to tradition in Native communities. This builds the future. It addresses trauma from the past and unifies different tribes and nations in the state. By using state funds to support community growers, the program gives tribal communities an opportunity to hold on to their cultural traditions in a way that is economically as well as environmentally sustainable.

These initiatives—and the broader aim of supporting sustainability through localized food systems—are vital for our future. Communities all across the state can participate in changing the infrastructure of our institutional food systems, thus ultimately changing policy. This aligns with everything that matters to me as a Native American chef serving locally sourced foods. When these same foods can be purchased and prepared in the kitchens of our schools, senior and elder centers, and Head Start programs, it creates a system that supports equitable access to fresh, locally grown food and supports small local farms and farmers who can now be a part of a new system as suppliers.

Think about it. New Mexico–grown food for schools. New Mexico–grown foods for senior centers. Local farms that provide these foods, all done with state money for these institutions to buy local, which then becomes policy for the future. The food systems change. Lives change.

And change is happening. In the 2019–2020 school year, the New Mexico Public Education Department reports that over $1 million dollars was spent by schools who invested in New Mexico–grown fruits and vegetables, and the average school district spent 15 percent of its produce budget on local products. An estimated 171,000 students across the state were served school meals featuring local produce, from tomatoes to green chiles to fresh salad greens. School garden programs are operating in eighteen schools and school districts to complement serving local food in their school cafeterias. Student-grown produce is served in seven school cafeteria settings. And sixty-four vendors sold to schools through the program, including distributors, grower cooperatives, and individual farming operations.

These collaborations increase marketing opportunities for farmers, strengthen farmers markets, and preserve agricultural traditions in Native and non-Native communities alike. They will also inform public policy and further New Mexicans’ understanding of the interplay between farming, food, health, and wellness while having positive impacts in our local economies. Increasing local procurement can have a multiplying effect: It helps small family farms keep cultural traditions alive; it provides children and seniors more access to fresh, local, flavorful food that is integral to health and wellness; and it helps make New Mexico a model for broader change as other states work to increase the health and wellness of their populations with locally sourced fruits and vegetables for generations to come.

For more information on any of these projects or work, contact the author at Red Mesa Cuisine (redmesacuisine.com), HKHC at nmhealth.org, Rita Condon at 505-476-7616, Siobhan Hancock at Siobhan.Hancock@state.nm.us, or Kendal Chavez at Kendal.chavez@state.nm.us or at 505-819-1984. Any small-scale farmer can contact Chavez to learn about trainings and the steps to certification for supplying locally grown foods to schools, senior centers, and other institutional buyers.

Edible celebrates New Mexico's food culture, season by season. We believe that knowing where our food comes from is a powerful thing. With our high-quality, aesthetically pleasing and informative publication, we inspire readers to support and celebrate the growers, producers, chefs, beverage and food artisans, and other food professionals in our community.