Artichoke Café’s David Gaspar de Alba Puts in Time at the Farm

Chefs work long, demanding shifts, often late into the night. But early one Sunday morning in May, Artichoke Café’s new executive chef David Gaspar de Alba arrived promptly at my door, ready to carpool to Polvadera, New Mexico, to help a farmer plant her summer crops. My husband, Seth, also a farmer, handed him a cup of coffee and the three of us piled into my car to make the hour-long trip south. I didn’t really know Gaspar de Alba, but I was already impressed that a chef would want to spend a rare day off working in a field. Over the course of the day, he continued to impress me with his culinary and farm knowledge, skillful cooking, and genuine passion for supporting local food.

Polvadera is a verdant historic farm community on the west bank of the Rio Grande in Socorro County. Most of the large family farms in the area specialize in livestock or in conventionally grown crops, such as green chile, alfalfa, and corn. However, Cecilia Rosacker’s twenty-eight-acre farm, Cecilia’s Organics, produces heirloom vegetables, such as eggplants, tomatoes, and beans, as well as dozens of flower varieties. Rosacker affectionately calls this little organic oasis “Polvaderadise.” As we pulled up to her property, Rosacker and a small handful of volunteers, including her son Carlos McCord, head farmer at Los Poblanos, were already hard at work transplanting pepper starts. Without hesitation, Gaspar de Alba grabbed a hoe and began making furrows in the soil.

“My love of food began with farming,” Gaspar de Alba told me. He grew up in El Paso, but every summer he would visit extended family in Benson, Arizona, and help out on their farm. “I was basically child labor,” he said with a laugh. “We’d sell pecans and produce by the side of the road. They raised cattle and rabbits. It was [instilled in me] that that’s the kind of food you should be eating—the type cared for in your backyard.” His interest in knowing where his food comes from was cemented in Portland, where Gaspar de Alba began his culinary career in 2003. His impressive resume in the Pacific Northwest included stints at the Screen Door, Portofino, Belly Timber, and celebrated sushi-spot Yakuza. “All the best chefs in Portland shop at the farmers markets,” he said. “They know which farms have the best of a particular item, and you have to show up early because it can be competitive.” When I asked how Albuquerque’s markets compare to Portland’s, he said, “It’s definitely smaller here. The soil in Oregon is so fertile and the [fruit and vegetable] varieties are limitless. Also, because the farmers make more money and have so much more product to move, they can afford to cut deals, sell in bulk—it’s very easy for restaurants to source locally.”

Since returning to the Southwest two years ago, Gaspar de Alba has become intimately aware of the struggles New Mexico farmers face growing produce in the desert. The chef initially relocated to Santa Fe to help create the menu and cook for Radish & Rye, which prides itself on local-sourcing, then moved on to Izanami at Ten Thousand Waves, where he could draw on his years of experience cooking Japanese cuisine. But in the summer of 2016, Gaspar de Alba decided to swap out his chef knives for a broad fork, and spent the season working for Silver Leaf Farms in Corrales. “I was looking for a different experience, and me and the guys at Silver Leaf have similar views about food. It taught me how hard [that work] is—here, especially,” he said. Even though Gaspar de Alba has since returned to the kitchen, he continues to be involved with the local farm community—as a patron, volunteer, and friend. “I hope to create opportunities for my staff to experience local farms as well,” he said. “Understanding where the ingredients come from makes you more excited to cook with them.”

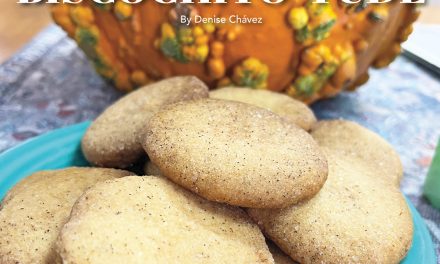

Left: Artichoke Café’s duck confit with black-peppered strawberries, snap peas, and beets. Right: scallops with black morels. Photos by Stephanie Cameron.

Rosacker also thinks it’s important for chefs to visit farms, especially at the planting stage. “Sometimes a chef will come to check out the farm when the crops are ready for harvest. But to see it on days when it’s just dirt, and experience the hard work that goes into making our dry, clay-laden soil [hospitable for plant growth], is important. Two months will go by before we have anything to show for the work we did [during Gaspar de Alba’s visit],” she explained. “Actually, I wish everybody who eats local food could experience it. I think there would be a much deeper appreciation for the challenges of growing things in New Mexico.”

At Artichoke, Gaspar de Alba acknowledges local food providers by listing many of them on a chalkboard in the dining room and by educating the servers on the provenance of the menu’s ingredients. “Whether it’s wild-caught Chinook salmon from northern Washington, lamb from Encino, or morels from the Sangre de Cristos, the story of the ingredients needs to be communicated to the customers. Diners who spend their money on sustainable and local foods are voting for restaurants to support those practices,” explained Gaspar de Alba. Since taking over Artichoke’s kitchen, Gaspar de Alba has been steadily incorporating new menu offerings and specials. “Some classics will remain on the menu, but we’ve seen a lot of new clientele coming in who want to try something more experimental,” he said. Gaspar de Alba’s dishes are flavorful but clean with a strong seasonal focus. For instance, in the spring, customers should expect dishes featuring local baby beets and pea shoots rather than heavy cream sauces. His background in Asian cuisine (most recently displayed in his short-lived but much-loved Oni Noodles food truck at Marble Brewery) also sneaks its way onto the menu: “I don’t want to do ‘fusion’ so I kind of hide it in there by infusing some of those umami flavors—from seaweed, fish sauce, miso—into something like lemon sage butter. Diners can tell there’s a great back flavor going on but can’t identify it.” He sees Albuquerque’s local food scene as a market primed for expansion and innovation, and he wants to be part of the cohort of chefs, farmers, producers, brewers, and distillers leading the charge. “It’s exciting and rewarding to be part of the change.”

After the volunteers at Cecilia’s Organics finished the planting that Sunday afternoon, Rosacker invited us all back to her beautiful adobe home, where she prepared Swiss chard red chile enchiladas and a farm greens and citrus salad. She handed Gaspar de Alba a pound of beef kidneys harvested from her cattle and asked if he had any idea how to cook them. “I don’t really know how to prepare kidneys,” she said, “but my African friends like to buy them.” Taking that cue, Gaspar de Alba took some Berbere spice mix out from the cupboard, made up a quick marinade with vinegar, salt, and sugar, then pan-seared the kidneys with the Ethiopian spices and New Mexico jalapeño powder. He finished his experimental dish with shaved raw red onion, baby cilantro greens, and a squeeze of lime. Everyone was blown away with how he was able to come up with something so delicious on the fly. We worked off the meal with a late-afternoon hike through San Lorenzo Canyon, only to follow up with fresh-baked cherry pie back at Polvaderadise.

Reflecting on having spent his day off at the farm, the chef said, “Hey, you can always do your laundry another day. Hanging out with people knowledgeable about food, eating, drinking, and talking (about food) is my idea of a great day. One of the best I’ve had since moving to Albuquerque, actually.”

424 Central SE, Albuquerque

www.artichokecafe.com

www.facebook.com/CeciliasOrganicHarvest

Candolin Cook is a historian, writer, editor, and former co-editor of edible New Mexico. She recently received her doctorate in history from the University of New Mexico and is working on her first book.