Brighten outdoor spaces with potted plants this season

By Marisa Thompson

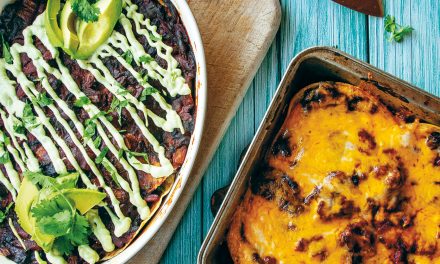

Container garden. Photo by Maksim Shebeko.

Container gardening is nearly as versatile as your imagination. Useful in small spaces, like a balcony or front doorstep, containers can also liven up the whole yard if you tuck them between existing perennials that have finished showing off this year.

Container plants can also be moved around to spots with optimal sunlight or more protection from the cold and wind. If yours aren’t thriving, and you know drainage isn’t the issue (more details below), try moving the container to a different part of the yard. And if a polar vortex is on the horizon, look up the cold hardiness of your container plants (how cold can they get before becoming frost damaged) and move those that are tender to a protected location—even indoors in extreme situations.

For just about any given plant, the roots are not as cold tolerant as the aboveground portions—because they don’t have to be. Soil acts as an insulator, protecting roots from wild temperature fluctuations in the surrounding air. The roots of container-grown plants are more vulnerable to cold injury because they’re more exposed aboveground. To protect plants from cold injury, whether potted or in the ground, consider these tips:

- Select species hardy enough for your area. Use the USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map at planthardiness.ars.usda.gov to determine what zone you’re in.

- Cover the root zone with a carpet of mulch several inches deep. Recommended mulch materials include woodchips, bark, pine needles, leaf litter, pecan shells, or any other fibrous, natural material you can access easily.

- Utilize microclimates. Walls—low or tall—can dramatically alter temperatures and wind exposure.

- Water less frequently in winter, but still saturate the entire root area about once per month, even if the aboveground tissues have died back (a few inches of snow may not be enough water).

- Be cautious with fertilizer. Nitrogen, in particular, can cause a flush of new growth in plants that are not yet dormant or don’t go dormant at all (e.g., roses, pines, nandina, etc.). New growth is especially tender and easily damaged by cold and wind.

Winter or summer, the biggest concern for container gardening (including houseplants) is drainage. Roots need both water and oxygen to survive. In waterlogged soils, sufficient oxygen cannot reach the spaces between soil particles where the roots are waiting. The best soils for containers are light and porous, and therefore well draining. At the nursery, look for products clearly marked as “potting soil.” No matter how permeable your soil is, if the drainage holes are clogged—or there are no drainage holes at all—roots will suffer sooner or later. Avoid putting gravel or sand in the bottom of containers because water does not drain easily from a fine-textured soil (like potting mix) to one that is coarser (like pebbles or rocks).

To get you growing in the right direction, here’s a list of plants for your outdoor containers. Thanks to several landscape consultants and online resources for their insights and inspiration.

Try native and adapted grasses like little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium), sand lovegrass (Eragrostis trichodes), Indian ricegrass (Oryzopsis hymenoides), and Karl Foerster feather reed grass (Calamagrostis × acutiflora). Others with beautiful foliage that persists into winter include beargrass (Nolina microcarpa), dianthus (Dianthus spp.), and coral bells (Heuchera spp.). Several conifers also perform very well in containers, depending on their heat tolerance and the pot size.

For a splash of color, pansies are tried and true but do require ample water. Mums have done remarkably well in the Learning Garden at the New Mexico State University Agricultural Science Center at Los Lunas, with relatively low amounts of water. Both pansies and chrysanthemums (a.k.a. mums) are edible, to boot. Ornamental cabbage is another colorful edible, albeit bitter; red and purple kales may be more palatable and just as bright.

Kale and cabbage, in fact, are just a few of many cool-season veggies that will continue to produce, as long as they’re protected. Depending on the weather and where you are in the state, that protection might mean a light frost cloth or sheet on colder nights, or it might mean a cold frame structure that traps solar energy (and requires ventilation on warmer days). Again, if your containers are easily movable, you can move them indoors for protection on a need-to-grow basis.

Another perk of early fall gardening: you’ll find some great deals on plants and pots once the heat of summer has begun to shift into the crisp cool of October.

Marisa Thompson

Marisa Thompson is New Mexico State University's Extension Urban Horticulture Specialist, responsible for active extension and research programs supporting sustainable horticulture in New Mexico. In addition to studying landscape mulches and tomatoes, her research interests include abiotic plant stressors like wind, cold, heat, drought, and soil compaction. She writes a weekly gardening column, Southwest Yard & Garden, which is published in newspapers and magazines across the state and on her blog. Find her on social media @NMdesertblooms.