Grandpa Pete’s Bean Bank

Words and Photos by Ungelbah Dávila-Shivers

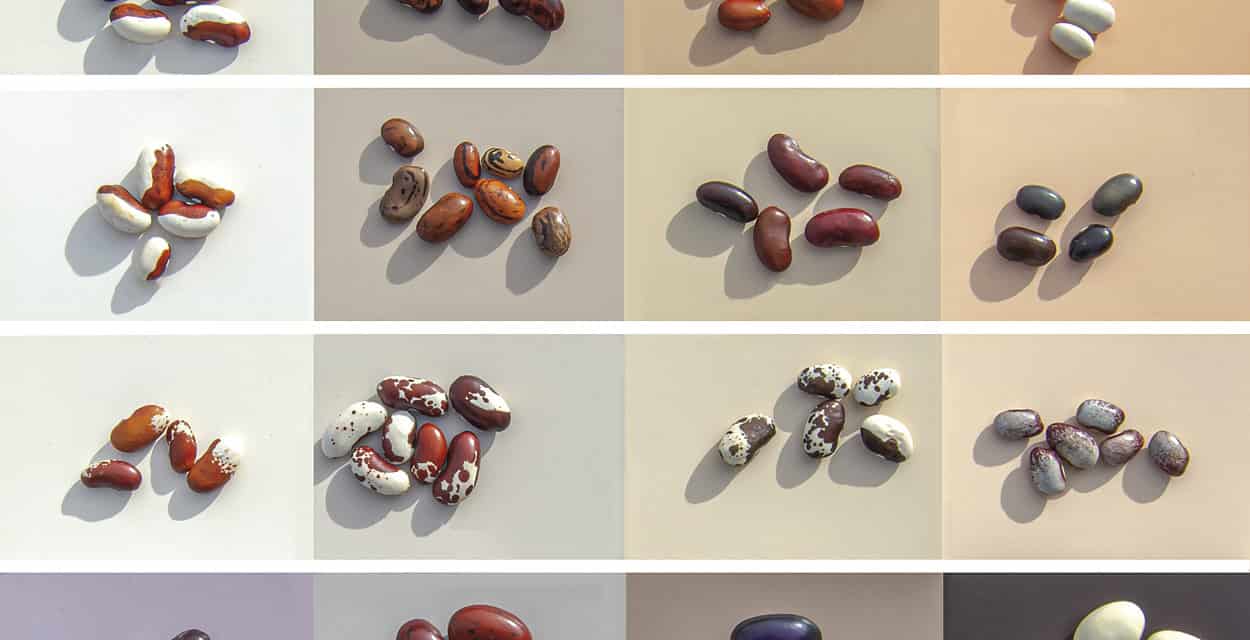

Collection of beans from Pete Daniel’s bean bank.

Beans. Yes, they can be noisy, but they’re also resilient, humble, diverse, and, well, they are tough as hell. In short: beans are the food of the people.

Have you ever walked into a home after a long day at school or work and been greeted by the smell of a pot of beans? I have—in the cabin where I was raised. In my nana’s yellow kitchen. In my best friend’s house, where her mother used a micaceous pot to cook them. In my first studio apartment in college. At my first house with a boyfriend. In the camper I lived in when everything went wrong. In the home I now share with my husband and children.

This is my love letter to beans.

Since I was born, the smell of boiling beans has filled every room I have ever gone home to, all across the Southwest.

Beans, which have now become a family of over four hundred cultivated varieties, were domesticated on Turtle Island so long ago that they have become a part of our Indigenous peoples’ creation stories. They are sacred. In one cup of cooked pinto beans, the human body receives 15.41 grams of protein, 15.39 grams of fiber, 85.5 milligrams of magnesium, 745.56 milligrams of potassium, 251.37 milligrams phosphorus, 78.66 milligrams calcium, and 244.53 calories, according to University of Rochester Medical Center.

First grown in the highlands and lowlands of Mexico and then in the Andes, the common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) is indigenous to the Americas and is considered the mother of almost all modern beans, including snap beans, dry beans, and shell beans. Of at least seventy wild species in the Phaseolus genus, all native to the Americas, three others were domesticated long ago: lima beans, runner beans, and tepary beans. Other types of legumes, such as chickpeas, lentils, and fava beans (Vicia faba), have been cultivated in Europe, Asia, and Africa for thousands of years.

When times were hard, and they’ve been plenty hard, beans have kept me alive—home-cooked, canned, or refried. I learned this from my ancestors’ survival. It’s imprinted in my DNA. You won’t die so long as there are a few beans on hand.

My father is a sixth-generation cattle rancher. When I had my daughter, I had trouble with my milk supply. He told me a story about how he had dry mama cows, so he started giving them beans. After a bean feast, they made milk like never before, so I started eating beans like crazy.

During my pregnancy, plagued by twenty-four-hour morning sickness for seven months, my unborn daughter and I survived on bean and cheese burritos. When my baby started eating solid food, who would feed her a bowl of mashed beans first became a competition. My mother won. It was a moment, because beans aren’t just food, they’re family.

There is no scent more nurturing, no flavor more life affirming, than that of a fresh pot of beans. Pintos, limas, Anasazis, Hopi string beans, scarlet runners—it doesn’t matter the kind, color, or language, every pot of dry beans boils with life.

I have a list of the scents that take me home, and among them are the St. Ives lotion my nana wore; the fragrance of sawdust, gasoline, and coffee that is my father; the aroma of the first monsoon rain carving into an arroyo; and an afternoon room greeting me with the smell of beans.

Tarahumara men outside a trading post in Mexico’s Sierra Madres in the late 1990s.

Water is life, but beans are its heartbeat. Beans are heroic. Beans are a thumbprint of our evolution on earth. Beans transcend class, culture, and time. They are not just a part of Indigenous survival; they have become part of our global survival. Little stinky ambassadors—how can you not love that?—wrapped in a tortilla and smothered in chile and cheese! Ay!

But seriously, could the Allied forces have had the strength to win World War II if not for the fuel of beans? Pinto beans that were cultivated in places like Estancia, Moriarty, and Mountainair. I want to believe that beans were a factor in all of our major triumphs, from the Pueblo Revolt to surviving Bosque Redondo, to me graduating college and having my first baby.

My first job was cleaning the beans. We lived in a two-room cabin that my parents had built by hand on the family ranch. The kitchen table was a butcher-block slab of wood on top of tall stumps. Despite its magnitude, it was something I associated with softness. It was smooth from meals prepared—the flour and Crisco of hundreds of tortillas, sugar cookies, and biscuits—and if I pressed my nail into its surface I could leave my own mark.

This was my perch, illuminated with the afternoon light that came in through miles of undisturbed ranchland onto the table where dinner would begin with me, the bean cleaner. Scattering a thin layer of pinto beans in front of me, I sifted through them, one by one, meticulously separating out the hard dirt clumps. I was vigilant in determining whether or not a bean met my qualifications before going in the pot.

It was the early nineties, but we didn’t have electricity. Mom cooked dinner on an antique propane stove built in the early 1900s. I loved the sound of the pressure cooker rattling and steaming, the smell of beans in the air signaling the nearness of satisfaction, of fullness. Beans, chile, tortillas, and elk sustained us through every season, and, along with warmth made from burning wood, protected our family against cold, hunger, and the outside world.

Throughout my childhood, I never knew my grandfather not to spend his summer nights in a hammock, strung between the walnut trees, so he could be alert to chase elk out of his garden. This garden was paradise, situated between the Frisco River and the Gila Wilderness. It was a garden that could feed a family. Some beans, like pintos, bolitas, and teparies, are suitable for dryland farming, and although big farms such as Ness Farms in Estancia, Schwebach Farm in Moriarty, and the Navajo Agricultural Products Industry in Farmington rely on drip and sprinkler irrigation, many Hopi and other growers still use dryland methods.

But Earnest Daniel, aka Grandpa Pete, had his own way of doing things. In the spring, Grandpa put his beans in dampened Mason jars that he slept with at night to keep warm. These were varieties he had collected all across the West, and some he had developed himself. After the harvest, he would sit at the kitchen table and lovingly admire his beans, each one beautiful and unique, in vibrant reds and purples, yellows and blacks, selecting the best of the best to store away for the years to come.

Earnest “Pete” Daniel. Photo by Rebecca Daniel.

Grandpa turned one hundred in 2022. We attribute his longevity to a steady diet of beans. Unfortunately, he isn’t able to tell me about his adventures in beaning anymore, but my mother helps fill in the gaps.

“Beans were Dad’s passion. He grew them, crossbred them, and played with them for years,” my mother, Rebecca Daniel, tells me. “He came up with all sorts of colors and shapes and types of beans. He was interested in this yellow bean that he called ‘Indian Woman Yellow.’ He had gotten it in Montana and said the Native Americans in Montana grew it for a shell bean.”

Grandpa was fascinated by this little yellow bean, which he said was grown all over the West by Indigenous people. Then he got his hands on a book about the Indigenous Rarámuri people of Mexico, also known as the Tarahumara, and learned about their farming ways.

“He wanted to go to the Sierra Madres and meet the Tarahumara to see if he could get that yellow bean from them to cross with the one from Montana, so as to strengthen the genetics,” my mama tells me. And so in 1999, she and my grandpa, who was seventy-seven at the time, along with their friend Jay Scott, caught a bus from Juárez to the city of Chihuahua. From there they took a train to the top of the Sierra Madres to a village where they were able to hire a cab driver.

“This guy took us in a cab for miles and miles out across the mountains through the woods,” remembers my mother. “I was just holding my breath that this cab wouldn’t break down or blow a tire or whatever because we were out in the middle of nowhere on this dirt road in the mountains. At the end of the road, there was a trading post, and when we got there all these Tarahumara men were sitting outside, smoking rolled cigarettes.”

At the trading post, they told the men about their bean journey, and, says my mother, “the locals pulled out all their seeds and gave my grandpa some big purple-speckled beans, a big white bean, and others, including the Indian Woman Yellow bean.”

“He brought home quite a stash of seeds and grew them. The Indian Woman Yellow bean had a particularly great flavor,” says my mother. “I really liked it, but he was never able to grow it in abundance to where I could have a lot to cook. Mostly he was doing it for seed, and he’s got quite a seed bank of beans.”

I remember dinners with my mother’s parents. They always involved a bowl of Grandpa’s beans, which began in all shapes and colors and ended up in a tasty soup, made tastier with freshly canned bread-and-butter pickles and some pepper jack cheese.

Grandpa irrigated his beans and the rest of his garden from a natural spring, a mile or more away in the Gila Wilderness. In his garden, he made pathways canopied with trailing beans, blooming in different colors. The big purple beans Grandpa was given by the Rarámuris bloomed brilliant scarlet and drew in every pollinator around. Today I’ve seen them labeled the scarlet runner bean, and sold in specialty bean shops like Rancho Gordo. But in Grandpa’s day, no one was growing beans like his.

In his seed bank is another unusual bean that looks like an Anasazi bean except it’s black and white rather than maroon and white. I’ve seen it called a vaquero bean and referred to as a cousin of the classic Anasazi bean, which Grandpa also grew. This particular bean was given to him by a friend who discovered it in a cave ruin, most likely left over from the Mimbres people who inhabited southern New Mexico from the tenth to the twelfth century, according to anthropologists.

As I sort through a bag of my grandpa’s beans, I’m captivated by the way each bean is unique, and yet how each one bears a slight resemblance to the others. Being close to twenty years old now, the vibrant purple beans he received from the Rarámuris have turned a color so deep as to be black, yet I can still see traces of purple in some of their descendants. I find incredible little beans with markings like those on Anasazi and yellow eye beans that also bear patterns of the larger scarlet runner beans and Hopi string beans. I’m told it is unusual for a common bean like the Anasazi to cross with a runner bean, yet it happened in my grandpa’s garden. Beans have been a survival food for so long, and I envision them feeding people into the future, persevering through changing conditions in the land. In other ancestral Puebloan and Mimbres ruins where beans have been found, they weren’t thousands of years old but were rather the wild descendants of beans grown in those ancient times. They, like people, carry the resilient DNA that keeps them adaptable, dependable, and one of our closest plant allies.

Ungelbah Dávila

Ungelbah Dávila lives in Valencia County with her daughter, animals, and flowers. She is a writer, photographer, and digital Indigenous storyteller.