The Legacy of the Fred Harvey Company

By Jason Strykowski

Not too long ago, the best food in the American West was served at a chain restaurant. These eateries crafted cuisine with continental and North American influences using fresh, local produce and imported spices. The fascinating meals arrived on the arms of properly trained young women carrying fine silver platters and were served miles from major cities. The Fred Harvey Company served some of the most cultured meals in some of the wildest parts of the United States. And the heart of their operation was right here in New Mexico. From Raton to Albuquerque, the Harvey Company promoted the unique flavors of the Southwest while inventing a system of hospitality that prefigured the modern chain business by decades.

Odds are good that anyone travelling in the West over the past century-and-a-quarter has crossed paths with the Harvey Company or its legacy. At its height, the Company controlled sixty restaurants and two dozen hotels along the rail line from Chicago to California. Later, they continued those services along the iconic Route 66 highway. For travelers headed west, the Harvey Company was the best, and often only, option for food and accommodations for a huge section of the United States.

The Harvey Company gained its relative monopoly by revolutionizing the hospitality industry in the United States. Stephen Fried, author of Appetite for America: Fred Harvey and the Business of Civilizing the West One Meal at a Time (2010), explains, “Before Fred Harvey there was really no standardization in restaurants and hotels. The Harveys became the first company to stop serving milk in pitchers and put it in a bottle with the top on it so that it might not kill you. Just a basic thing like that did not exist anywhere.” Little things, like quality control, kept the Company atop the American cuisine market for nearly a century, from 1876 to 1968.

Fred Harvey, the namesake and founder of the Company, was also the epitome of the American Dream—a rags-to-riches success story who fashioned himself from poor immigrant to entrepreneur. Born in England, Harvey arrived in the United States at the age of fifteen. He got his first taste of the restaurant business in New York lunchrooms as a dishwasher, but took careful note of the way that these lunchrooms worked. Harvey put this knowledge to work as a young man newly relocated to St. Louis, Missouri. Unfortunately, the Civil War destroyed his fledgling restaurant and Harvey sought opportunity elsewhere.

Harvey moved to Leavenworth, Kansas, where he secured a job working for the railroad as a clerk. While in this position, Harvey spotted an opportunity to once again tempt his fate in the restaurant business. The relatively new transcontinental lines had little to offer in comforts west of Chicago. Some rail cars in the East sometimes served fine foods, but in the West, the occasional watering stop had only stale foods that often arrived so late that customers could not eat before boarding their trains. To avoid these poor lunch counters, travelers on multi-day journeys often packed their own meals. Harvey knew that if he could bring New York–style lunchrooms to whistle-stops in Kansas, he had a good chance of turning a profit.

Harvey began in Kansas, where he installed chefs hired from fine restaurants in Chicago. Beyond the preparation, the restaurants also focused on bringing in local produce. Managers at the Harvey restaurants stayed current on the yields from nearby farms and ranches. Failing all else, Harvey Houses would be the place to get affordable and plentiful cuts of beef. “The company began for many years in very small wooden train stations just trying to serve perfect, fresh steak and fresh vegetables—simple food that was not available fresh in most of these places,” says Fried. Options opened up considerably when refrigerated rail cars became available. The Harvey Company could then serve seafood in the heartland and make highly prized oysters available all along the rail. Harvey Company restaurants were frequently the best, or only, dining establishments in their hometowns.

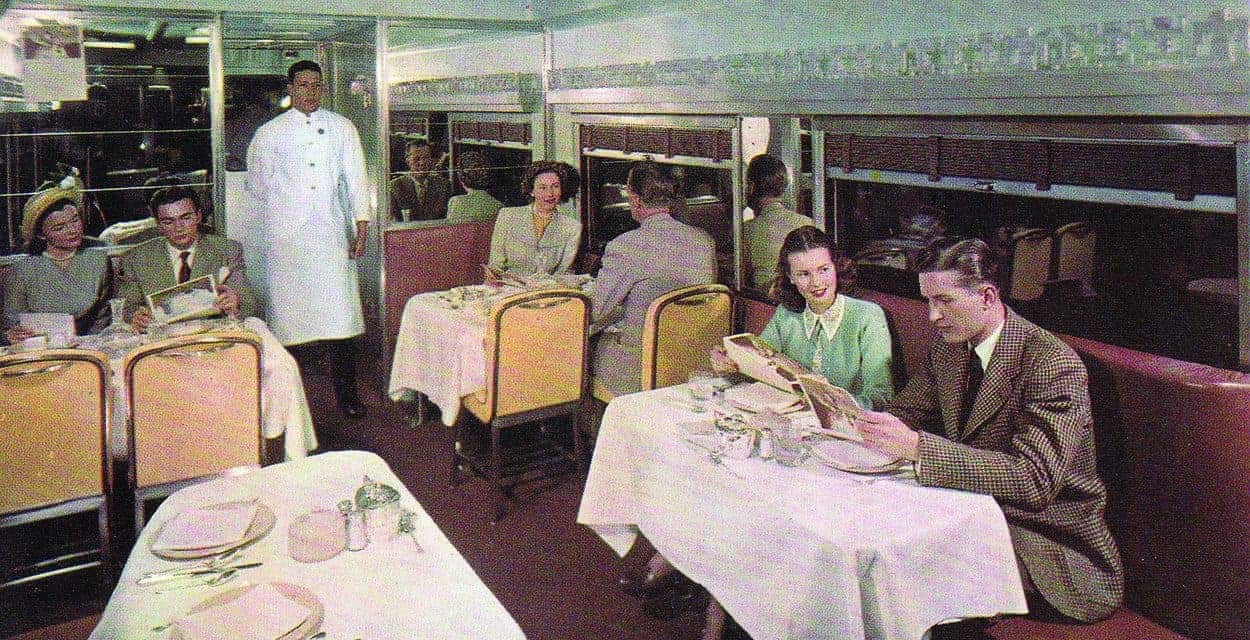

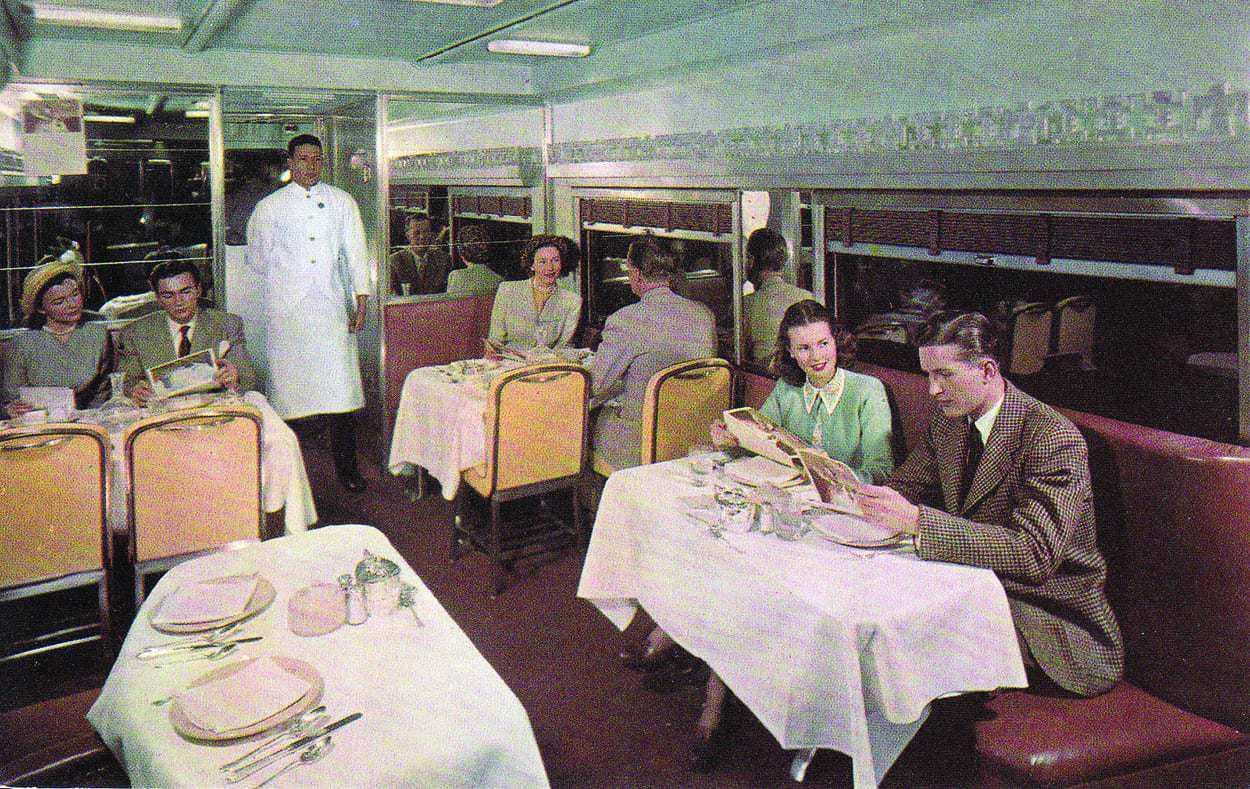

As it expanded, the Harvey Company had several classes of eateries under their umbrella: dining cars, lunchrooms, and formal restaurants. The formal dining rooms had a strict dress code while the lunchrooms were more relaxed. Perhaps the most important and uniform item on all their menus was coffee—which had to be remade every four hours. Beyond that, the choices could vary greatly.

The Harvey Company had good reason to make their menus both exotic and familiar—they had to feed customers multiple times at many stops along the railroad or the highway. In a single day, a traveler could sample continental flavors mixed with Mexican and Southern home-style cooking, and not grow tired of any of them. Other travelers might be stationed at a Harvey hotel for days and need good reason to continuously visit the expensive dining room. “The Fred Harvey Company always had the same service, they always had the same quality, but they always had changes in the dishes because they were there to keep people interested,” says Fried. “The idea was to make people excited about food.” Corporate headquarters sent revised menus to branches along the rail every four days to ensure that the eating experience never became repetitive. The Harvey Company also had the unique challenge of having to provide their food quickly enough to keep their customers on the move. Most rail riders had just thirty minutes to eat.

Many of the Harvey Company menus and recipes still survive. Some of the recipes were published and given to travelers on the rails; others were passed out only to chefs. The Company showed off its flavors in a cookbook printed circa World War II and gifted to riders on the Southwest Chief line. Recipes included ragout of lamb’s kidney piquante, stuffed zucchini andalouse, roulade of beef, and chile relleno. The book also included more conventional foods like blueberry muffins and navy bean soup.

By modern standards, most of the Harvey recipes were relatively simple. Even the exotic chile rellenos, as prepared by the famed Santa Fe-based chef Konrad Allgaier (the German-born Allgaier trained in Europe and served the German Army during World War I before emigrating to the United States), only called for five ingredients: chiles, American cheese, flour, egg, and butter. The dishes were, perhaps, intended to stretch travelers’ imaginations more than their palates. Chef de cuisine for the Santa Fe School of Cooking Noé Cano, along with chef Michelle Chavez, held a Harvey Company dinner at the school this past October and prepared albondigas, chicken Lucrecio, and a hot strawberry sundae on sour milk biscuits—dishes once prepared at La Fonda during the high Harvey days. “This is something I did for the first time and the response was excellent,” says Cano. “It’s really simple for us [to recreate], but really tasty. It’s not many ingredients. Back in the day they didn’t use as many seasonings.”

The food, however, was only part of the Harvey dining experience. The Company was legendary for its Harvey Girls. These young women, all between the age of eighteen and thirty, were recruited, then trained and moved to stops along the Harvey system. The women dressed conservatively in long black dresses and white aprons. They were a striking sight in towns that often had few people and fewer women. The Harvey Girls became an emblem of the Company and were eventually immortalized in film. A 1946 Judy Garland musical, titled Harvey Girls, capitalized on the romance without delving too much into the facts.

The heyday of the Harvey Company and its decline were not far removed. Two decades after the Garland film, the Company ceased most of its operations and the family sold their remaining interests. A number of Harvey Houses still survive, most notably the two lodges at the Grand Canyon: El Tovar and the Bright Angel Lodge. Both were purchased directly from the Harvey Company and still celebrate the company’s work.

In New Mexico, in many ways the center of the Harvey empire, the legacy endures. The Harvey tradition is visible at La Fonda in Santa Fe, at the Montezuma Castle in Las Vegas, and at the Belen Harvey House. For the past five years, the New Mexico History Museum, in concert with the Santa Fe School of Cooking, the Plaza Hotel, and other New Mexico businesses, has celebrated a “Fred Harvey Weekend.” The food and the dining experience always play a central part in remembering the Harvey tradition. Meredith Davidson, nineteenth- and twentieth-century collections curator at the New Mexico History Museum, says, “From the beginning, the ethos was really to raise the level of the dining experience to a consistent and safer level and to have finer dining along the railroad.”

Long before chain restaurants became tantamount to industrial eating, the Fred Harvey Company oversaw a food empire while keeping their options and ingredients local. “They proliferated lots of different kinds of food. Before the 1920s very few people ate in restaurants, at all. It just wasn’t a common thing to do in America,” says Fried. While the railroad brought Americans to the West and Southwest, the Harvey Company let them taste it.

Edible celebrates New Mexico's food culture, season by season. We believe that knowing where our food comes from is a powerful thing. With our high-quality, aesthetically pleasing and informative publication, we inspire readers to support and celebrate the growers, producers, chefs, beverage and food artisans, and other food professionals in our community.