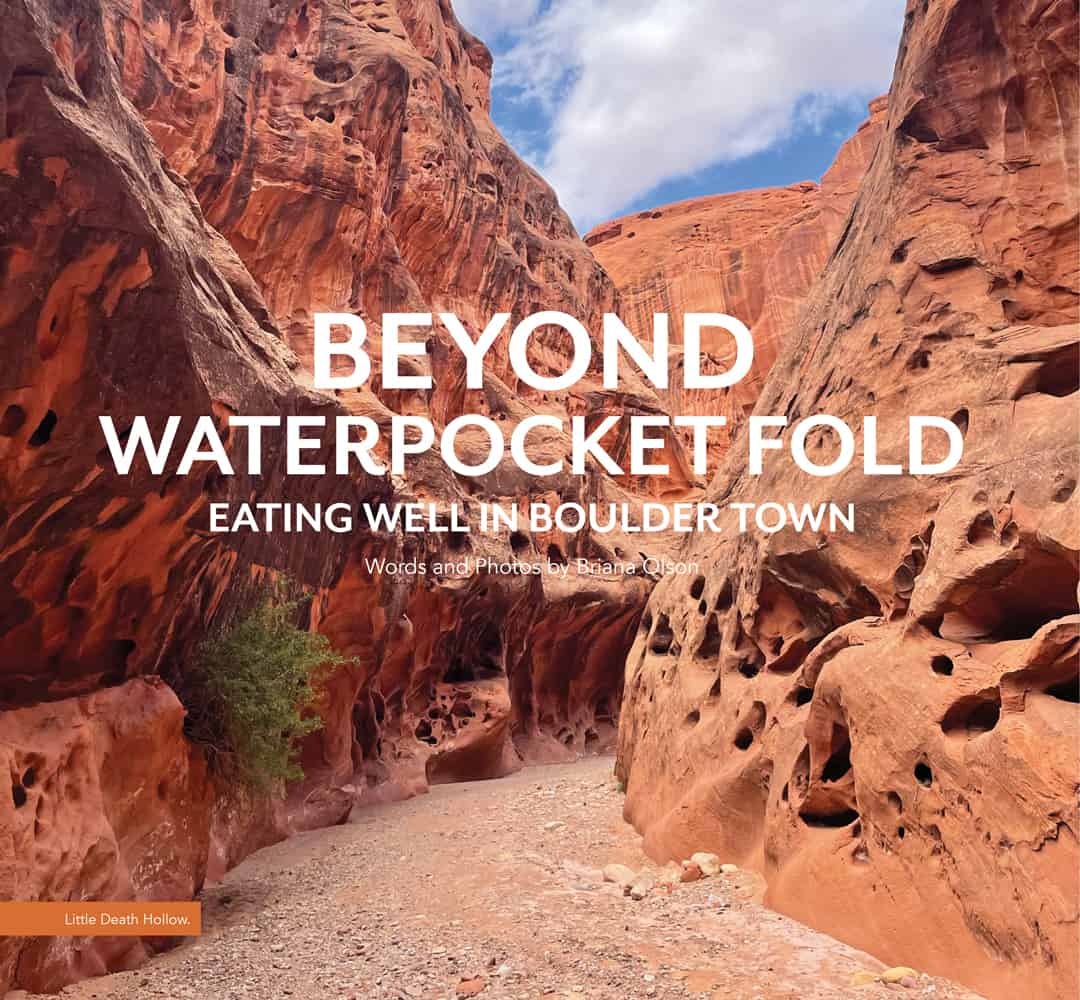

“Hope you enjoyed your Little Death trail,” my sister texted after reviewing the itinerary I’d left behind while on a visit to Boulder, Utah, in May. Little Death Hollow—not to be confused with Death Hollow, or Carcass Canyon, Devil’s Garden, Burning Hills—these are the types of names that draw one’s attention on maps and signposts of the area, and that few outsiders writing about the region can resist. And it’s true, as Blake Spalding of Hell’s Backbone Grill & Farm would tell me, that most of Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument’s 1.9 million acres are inaccessible to the average—perhaps even to the exceptional—human. But the names, as much as they hint at the mortal risks of tracing the passageways that water has cut into the Aquarius Plateau, reflect geologic features (naturally occurring coal fires, in the case of Burning Hills) and the sensibilities of surveyors and Mormon settlers. In Boulder Town, in the late nineteenth century, those settlers brought cattle. To whom they sold it, how they slaughtered it, what else they lived off, I don’t know, but I do know that Burr Trail, whose dusty switchbacks pass through the fascinating bend in the earth’s crust that John Wesley Powell named Waterpocket Fold, was built to run cattle and to take them to market. The trade routes of the Ancestral Puebloans who lived here centuries before Powell’s second expedition mapped this region on paper are harder to trace, but based on the ceramics they left behind, they’d traded with the people of Mesa Verde and Chaco, among many others.

Above: Chefs Tamara Stanger, Blake Spalding, and Jen Castle of Hell’s Backbone Grill & Farm, photo by Ace Kvale. Top right: Exterior of Hell’s Backbone. Middle right: Hell’s Backbone Farmstand. Bottom right: Dinner Pie and Crispy Farm Squash Salad from Hell’s Backbone.

“My hope,” Spalding said to me, “was that people would come here and fall in love with it and then they would fight to save it. And that’s what happened.” I’d asked if she worried about increased visitation to the monument. Like many who agree with her assertion that “human beings need to connect with wild places in order to understand their place on this spinning planet,” I don’t necessarily want every last human being to know about the wild places I most treasure. Moreover, I understand that the people of Boulder are wrangling with the challenges of sustainable growth, meaning growth that sustains them economically and socially while also sustaining the character of the town. Implicit in my question was another, internal one: Should I even be writing of this enchanting place?

The Civilian Conservation Corps didn’t build Hell’s Backbone Road until 1932. Before that, there was what’s now called the Boulder Mail Trail, a path that passes through pinyon-juniper woodlands and then traverses miles of petrified sand dunes, descending steep switchbacks of sweeping white cliffs into Death Hollow and then climbing up the other side to eventually reach Boulder Town’s closest neighbor, Escalante. The first time I hiked this trail was after heavy rains, and reeds and young willows lay flattened and rumpled like the hair of someone sleeping in the bed of Death Hollow. The water was so turbid that it clogged my partner’s water filter, and we had to climb out again early the next morning. Along the way, I photographed what remains of the telephone line that connected Boulder to a switchboard in Escalante in 1910. It hardly seemed possible that such a flimsy cord could transmit spoken words, much less be considered communications technology. But until I emerged from the trail and approached the cell tower near the intersection of Highway 12 and Burr Trail, the phone in my backpack was of no more use than the old line.

HELL’S BACKBONE GRILL & FARM

20 N Hwy 12, Boulder, Utah, hellsbackbonegrill.com

“President Clinton had just recently designated the monument that Boulder is an inholding inside of,” Blake Spalding told me of her and business partner Jen Castle’s decision to open their restaurant twenty-three years ago. “At the time there weren’t even the words ‘farm to table,’ but I had a strong belief in doing only local, place-based.” Restaurants centered on local sourcing existed mostly on the coasts, and Spalding didn’t want to start one someplace like her hometown of Flagstaff or even Albuquerque, where Castle had grown up cooking with her extended family.

“Our food systems in this country are so broken and anonymous,” she said. “I wanted to be part of a movement to change that.”

Castle and Spalding met while cooking for rafting trips through the Grand Canyon, and they’d just done a stint cooking for the Discovery Channel in the Pacific Northwest. Their experience cooking with “no resupply and no infrastructure,” having to filter all drinking water and dishwater and heat the dishwater up over propane, along with the moxie and work ethic both had from growing up with limited means, primed them for at least some of the challenges of starting from scratch in a conservative town perched on the edge of an aspen- and lake-studded mountain almost no one had heard of.

Hell’s Backbone bills its menu as Four Corners cuisine. What that means? No oceangoing fish, for one. Trying to source from the Four Corners region; digging into the history of the place. Using flavors and notes, like sage and juniper, that are relevant to the area.

“We’ll never be able to grow enough onions—there’s a limit to what we can do, and we’re at seven thousand feet. But in a typical year we grow several tons of food,” Spalding said. They’ve paid people to farm from the restaurant’s inception—the current farm manager, Kate McCardy, has been with them for about ten years—expanding from an onsite garden to Spalding’s home to the 6.5-acre farm they bought in 2006. They also have about a hundred chickens who “eat all the scraps and provide most of our eggs.” Because of the limited growing season, they have to think forward; last year, they grew blue Hubbard squash and stored it over winter to open with in spring. In late May, when we spoke, they were harvesting asparagus, quelites, herbs, and more, and anticipating a—literally—fruitful summer season, with elderberries, blackberries, currants, and all manner of heirloom stone fruit, from sour pie cherries to clingstone peaches to apricots of many sizes and flavor profiles. Spalding assured me that while the crab apple jam that I’d just fallen in love with—think the reddest, tartest apple butter you’ve ever had—was about to run out, they were expecting an abundant crab apple crop and there would soon be more.

The restaurant is independent, Spalding emphasized, chef- and women-owned, and committed to fair wages. This season, Chef Tamara Stanger, known for cooking with foraged wolfberries and mesquite pods in the Phoenix area, joined their team. That doesn’t mean Castle has absconded from the kitchen; the Jenchiladas, along with specials that often bear traces of her New Mexico roots, still appear on the menu, as does Spalding’s signature meat loaf.

Visiting in May, I was keen to sample one of the dinner pies that Stanger has introduced to the menu. For logistical reasons (namely, a canine traveling companion with limited social skills), I ordered takeout rather than dining at the restaurant. With another six-time James Beard semifinalist/nominee, that might have felt like a misdemeanor, and I did experience a twinge of regret observing the care guests were receiving in the dining room, a space that feels upscale yet also easy, peaceful, light. But in eating their food at a nearby campsite, I felt I was tapping into Spalding and Castle’s backcountry-cooking roots. And besides, aren’t pies some of the original picnic food of the West? This one seemed to encapsulate the notion of Four Corners cuisine: a pie of pure meat, good, locally pastured beef braised with love in a mole imbued with a tangy hint of American barbecue. The crust was exceptional: hefty yet light, built to survive a little time on the road (although they don’t typically offer the pies to go), but buttery, flaky, even elegant. I paired it with a glass of biodynamically farmed Mendocino red that I’d picked up at the package store at Hills & Hollows market (also the town’s one-stop shop for gas, ice, local beef, kettle chips, and other sundries).

Like many others, the restaurant has slowed down since the pandemic: they no longer do breakfast and serve dinner five nights a week instead of seven. (Signature pancake mixes, among other breakfast staples, can be procured at their farmstand or online shop.) But Spalding’s convictions remain much as they were when she and Castle started the restaurant. “What is sustainable,” she said, “is don’t go beyond your capacity, don’t exploit your staff, don’t exploit the planet, don’t exploit the land.” “We try,” she added, “to center love.”

Above: Hills & Hollows market. Right top: Lacy Allen at Wild Indigo Café. Right bottom: Lemon ricotta dosa and dosaquiles at Wild Indigo Café.

WILD INDIGO CAFÉ at Hills & Hollows

840 W Hwy 12, Boulder, Utah, hillsandhollowsmarket.com/wild-indigo-cafe

“Do you have a reservation?” Lacy Allen was asked when she and a friend first stepped into Hell’s Backbone Grill, dirty after a big hike. Despite having traveled to Boulder specifically for the purpose of eating goat cheese fondue at the famed restaurant, her answer was no. But like many a dirty pair of hikers who turn up there, they got a table anyway. Then Allen’s plan to set her friend up with the bartender led to her setting him up with herself. A year later, she moved to Boulder and started as a server at Hell’s Backbone, working up to dining room manager for a total tenure of seven years. (The bartender, now her husband, still works for the restaurant.)

I knew none of this when I approached the counter of Allen’s six-week-young Wild Indigo Café food truck and picked up a Mother’s Day menu featuring french toast, sweet dosas, and something called dosaquiles. Brightly painted, with a “mural coming soon” sign in the only space left blank, the truck’s design—like the food—draws some of its inspiration from India. It also evokes the visual surprise of hot-pink Utah penstemon. Seated at the small orange tables parked around the truck were a mix of visitors and locals; the couple ordering ahead of me had worked with Allen at Hell’s Backbone. Skeptical of the dosa-quiles—wouldn’t dosa chips get soggy in a tomatillo kimchi salsa?—I ordered a lemon ricotta dosa, then snagged bite after crunchy, aromatic bite from my partner’s plate.

“I was just obsessed,” Allen told me of her first trip to India, made possible partly because Hell’s Backbone Grill, like much of Boulder, closes every winter. “Everything was so colorful and smelled amazing; there was so much culture and beauty everywhere.” On her next trip, she brought a duffle bag. She’d been pickling from her home garden, and she started filling the bag with spices from every tea and spice vendor she came across. In Jaipur, she met one with “walls and walls of spices” who said he could ship anywhere. She started pickling carrots with turmeric, cauliflower with garam masala, and selling them at the farmers market. “Then COVID happened, and Hell’s decided [they were] never gonna do breakfast again,” and Allen hatched the idea of opening a breakfast place.

Last year, Allen reached out to Shawn Owen, the owner of Hills & Hollows market, about the food truck sitting idle in his lot. Their partnership includes an agreement for Wild Indigo to source beef from his family ranch. She also sources greens locally and continues to buy the bulk of her spices from her partner in Jaipur. For her, sourcing spices ethically means not buying from Amazon or other big companies where the origins of the product are rendered completely anonymous. Allen conceives most of the recipes, but credits head chef Garrett Compton with helping her execute ideas like the dosaquiles.

Noting that Garfield County has one of the lowest average incomes in the state, Allen said that while she wants to make enough to survive, she doesn’t want anyone to be priced out; the vision is to serve locals as well as tourists.

Left top: View from the patio at Burr Trail Grill. Left bottom: Lemon caper salad. Above: Reuben with house-made corned beef and seasoned potato wedges.

BURR TRAIL GRILL & TUMBLEWEED COFFEE

10 Hwy 12, Boulder, Utah, burrtrailgrill.life

The patio at Burr Trail Grill offers views of cattle grazing on an irrigated pasture, and there are lamb eating grass around the next bend, but I’m not surprised when owner Nichole Shrives tells me that it’s four hours round trip to buy meat from the butcher. In fact, given Boulder’s remoteness, I’m surprised it’s not farther. “Being out here,” she said, “we have to rely on [Nicholas & Company, an intermountain food distribution company] to some extent.”

They brine and slow-roast the corned beef for their reuben in- house, and do a lemon caper salad that has become for me on long hikes what lemon Snapple was to Cheryl Strayed on a certain stretch of the Pacific Crest Trail. The lamb burger is dressed Greek, and other sandwiches wear traces of Thailand. “We like using unique flavors and tying them into classic American dishes that you would expect coming to a place like this,” Shrives said of her and her husband Max’s culinary inspirations. Their care for consistency and quality, even when ingredients are not local, is evident. “One reason we have been able to do that,” she said, “is that we’re family owned. My sisters work here with me, my sister’s husband, and now my mom.”

Although the family lives in Boulder year-round, the restaurant’s overhead prevents them from staying open during winter, when the de facto population drops below two hundred. But Shrives hopes to keep their new venture, Tumbleweed Coffee, open all year. The café, located next door, opens this summer and will offer pastries and croissants in the morning.

Left: Magnolia’s Street Food. Right: Kimchee Breakfast Taco and Pancho & Lefty’s Burrito at Magnolia’s Street Food.

MAGNOLIA’S STREET FOOD

460 Hwy 12, Boulder, Utah, magnoliasstreetfood.com

Operating from a bus parked in front of the Anasazi State Park Museum, Magnolia’s Street Food serves breakfast and lunch. Alas, the Red Dirt Girl sandwich is no longer a standard option (it is offered at their new brick-and-mortar location in Escalante), but they often have lunch specials in addition to their array of tacos and burritos, which at lunch can be filled with a picadillo made from local beef. Co-owner Garin Apperson said that he’s drawn to make “good, simple, traditional food.” While he and his wife, Haylee, partner with Halfacre’s Farm to source some produce for their Escalante location, Apperson stressed the challenges of sourcing locally in Boulder. The couple no longer live in town, but some of the truck’s staff do. One friendly employee said he first came to attend the local survival school, and the man who cooked our breakfast dropped anecdotes about his time in New Mexico as the two chatted. “You forget how much of New Mexico there is,” I heard him say—a statement that could equally be applied to Utah.

Even though my understanding of geology is elementary, I can sense, in and around Boulder, that I am looking at a cross section of the history of the world. It is a place of extravagant and sometimes stark beauty. And maybe that makes it a good place to consider one’s place on the planet, now and into the future.

Lower Calf Creek Falls.

Travel Notes

Highway 12 can be taken in most any vehicle with a full tank of gas and a functional spare (and as in rural New Mexico, a good supply of water is never a bad idea), but remember that despite the good eating, this place is remote. Research and prepare appropriately before you venture onto hiking trails and sandy back roads. Also, know that Boulder’s climate is more like that of Taos than Phoenix, with summer highs in the low eighties—just take extra care when planning hikes during monsoon season.

Briana Olson

Briana Olson is a writer and the editor of edible New Mexico and The Bite. She lives in Albuquerque.